Goodbye, and good luck!

In 1872 contact between San Francisco and Glarus stopped. It seems Rudolph Heer wanted to finally cut all ties to his old life …

n 25 September 1868, Rudolf Heer and his family reached San Francisco. This is where the family from Glarus planned to start a new life. Scarcely had they arrived in the Californian city, however, than their lives were thoroughly shaken up.

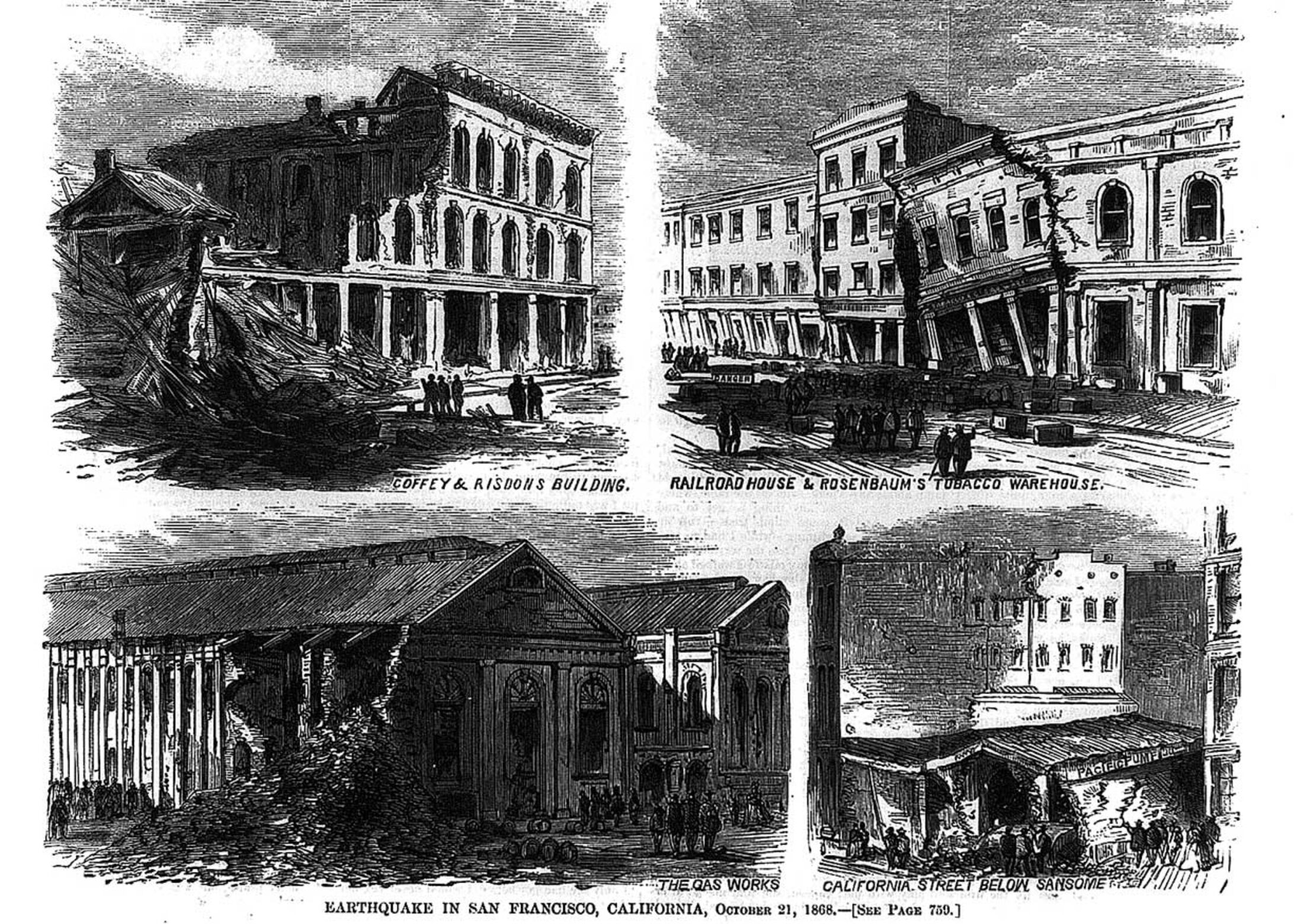

“On 21 October at 8am there was a terrible earthquake; everyone jumped out of the houses to get away, but many were struck dead in the street by collapsing buildings or high chimneys. Many people didn’t make it out. It was most dangerous in the city streets; scores of houses have collapsed on every street. In some places the ground was raised a few feet, and in other places the ground subsided a great deal.”

The Heer family experienced the violent earthquake, which measured 7 on the Richter scale, at first hand. Many people fled inland for fear of further earthquakes. There was extensive damage, and a great deal of work as a result. Rudolf, who now went by the name Rudolph, benefited from this. He finally found a job and an income for himself, his wife and their two daughters.

Photograph after the earthquake in 1868. (Wikimedia)

Illustration of the earthquake in San Francisco in Harper’s Weekly, November 1868. (Library of Congress)

In the years that followed, Rudolph Heer worked as a sawyer, a millwright and a machine operator, among other things, and in May 1869 he wrote to his mother:

“As far as I and my family are concerned, we are pleased so far and lead happier lives than in our old homeland.”

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

And the man from Glarus had big plans. He wanted to become an American citizen and buy land. The “Homestead Act” of 1862 allowed people over the age of 21 to mark out and farm an unsettled piece of land of around 64 hectares. After a five-year period, the settlers then became the owners of the land. However, you had to be an American, or stand a good chance of becoming a citizen.

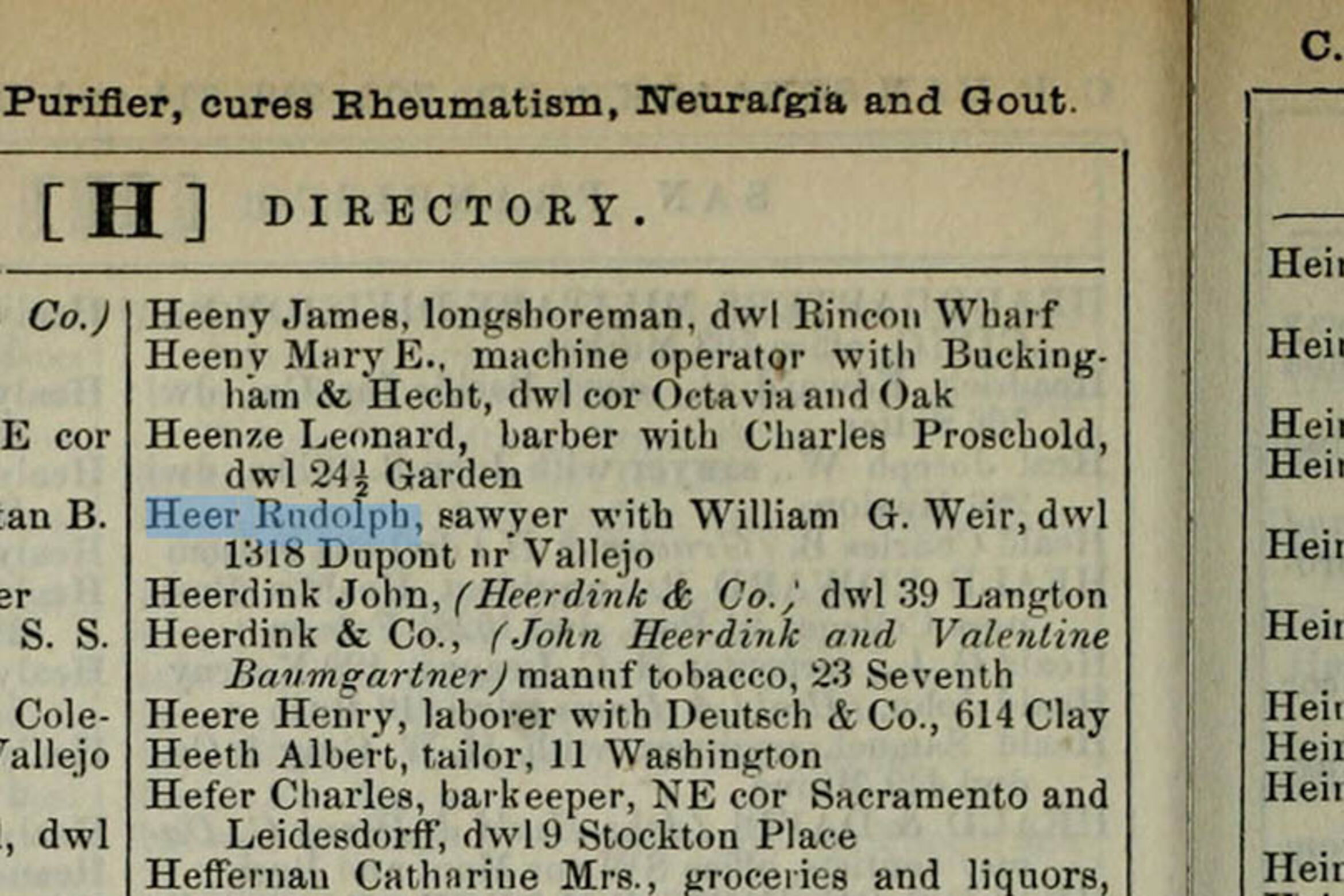

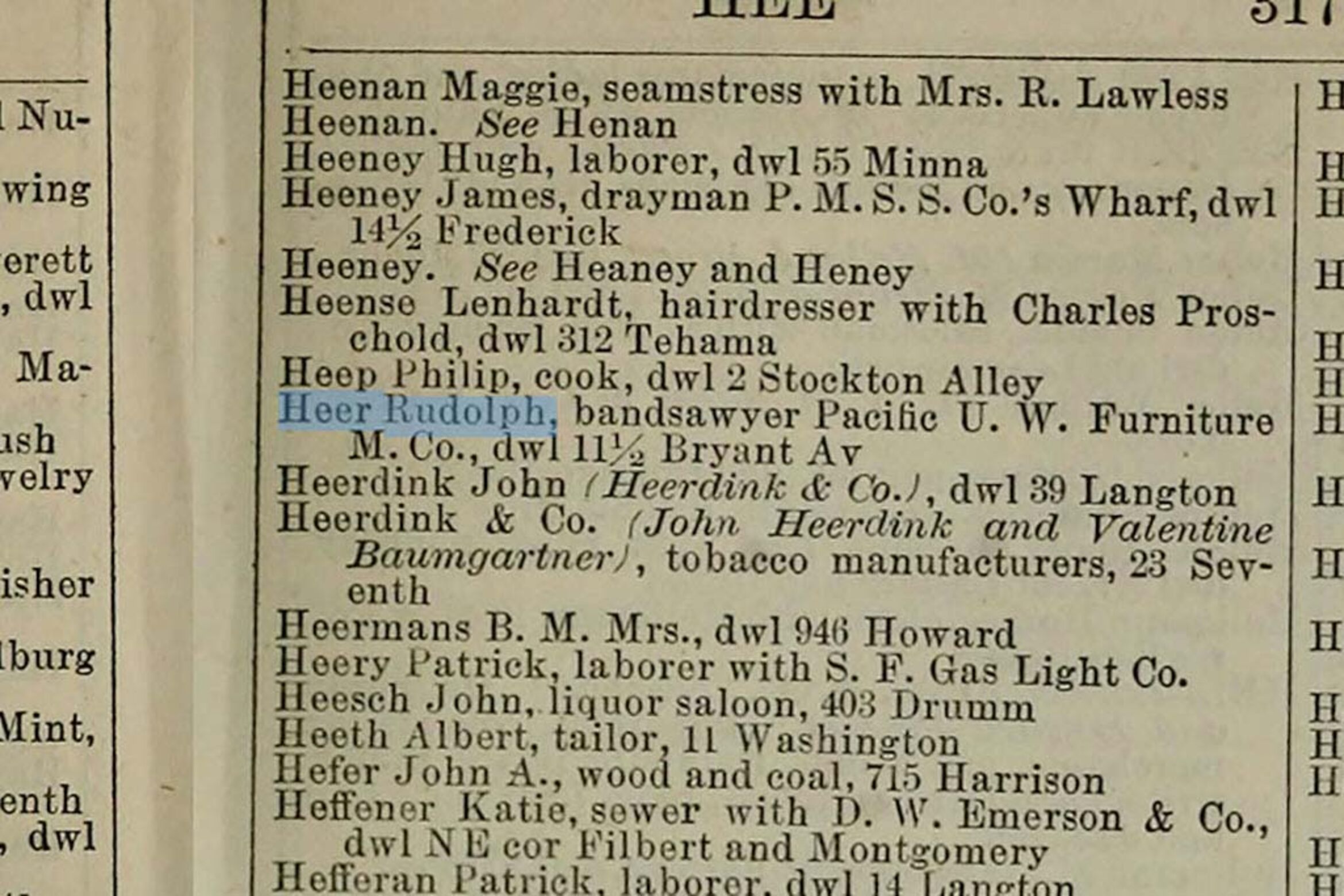

With the help of various entries in “Langley’s San Francisco Directory”, a name and trade register, it is possible to build a fairly accurate picture of Rudolph Heer’s career. (Internet Archive)

That all sounded highly promising. But reading between the lines, a different story emerges. In the five letters that Rudolf Heer wrote to his mother between 1868 and 1872, money was the main topic. Again and again, he compared the prices in the USA with those in Switzerland, pointing out how much various items cost and who owed him money or to whom he owed money. Even when Maria, his younger daughter, became seriously ill, all Rudolf was concerned about was the amount of the doctor’s bill:

“Marieli has been ill with pleurisy for 3 weeks. She was so sick that we had quite given up hope of saving her; now she is on the mend. If you go to the doctor it costs 3 dollars, if the doctor has to come to the house, each visit costs 5 dollars, and then you go to the pharmacy for the prescription, where you have to pay extra. So sometimes you leave it too long before you go to the doctor.”

Not a word of concern for the child. It seems as if Rudolph Heer just couldn’t make any headway financially. Whether they were leading “happier lives than in our old homeland” seems more than a little doubtful. Later on, he also abandoned the plan to purchase land.

“I’ve given up my decision to take land for the time being, and I’m doing pretty well here and I’m happy so far."

Letters from the New World

Rudolf Heer emigrated to America from Glarus in the 19th century. Between 1868 and 1872 he sent a total of five letters back to his old homeland. The letters are now in the archives of the Heer family, along with a number of other documents. This article is based on those letters and on research carried out by Fred Heer, a descendant of the Heers who stayed in Glarus.

It’s also striking that, in addition to the subject of money, most of the content of Rudolph’s letters revolves around the old homeland. Glarus here, people from Glarus there. California and the Heer family’s new life are seldom mentioned, and when they are the references are usually cursory and indirect:

"However, it would be best for every young boy if he went to America for a few years for an apprenticeship, because everyone has to learn here and also gets to know the world and mankind, as is not the case abroad.”

By “abroad” he means the old homeland – in Heer’s case Glarus. In his opinion, almost everything is better in America than in Switzerland. For example, as a worker you earn more, and you’re treated with more respect:

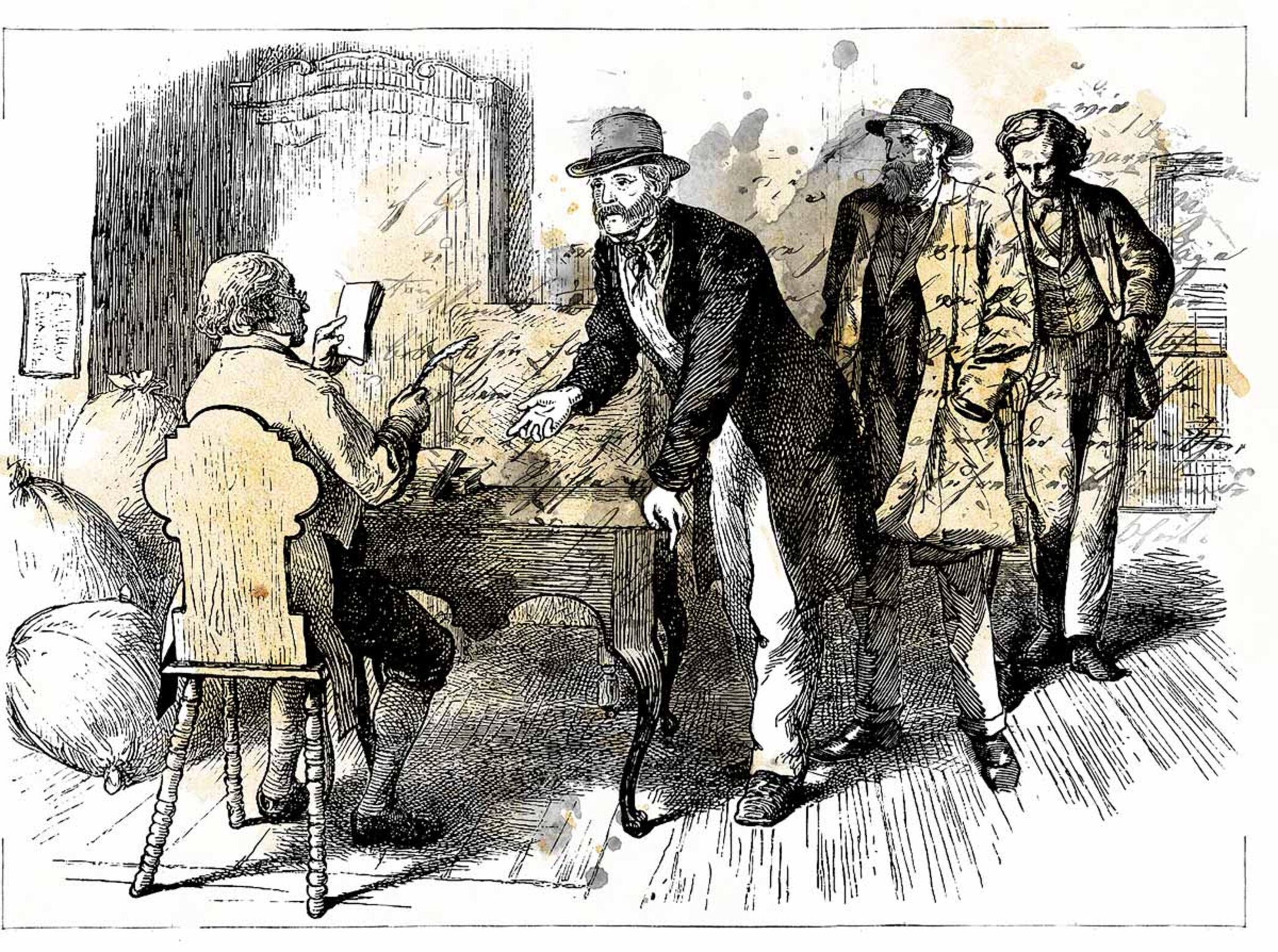

"Here the worker is more respected than abroad and is also paid properly for the work, and you don’t doff your hat to employers or millionaires; instead, you go to the office on Saturday evenings with your hat on your head and receive the money you’ve earned for the week.”

Being able to meet with his employer without removing his hat impressed Rudolph Heer. (Illustration by Marco Heer)

Nonetheless, Rudolph didn’t want his youngest brother Samuel, who was training to be an engine driver in the 1870s, to come to America:

“However, I’m not writing to brother Samuel that he should come to America because if you’ve been here for a few years, you can no longer really deal with the conditions abroad; nobody likes it abroad anymore.”

Was he trying to prevent Samuel from seeing how things really were with Rudolph Heer and his family? It almost seems so, because this would be the last letter to his mother. After that, contact broke off, although Rudolph lived on for another ten years and only died in 1882.

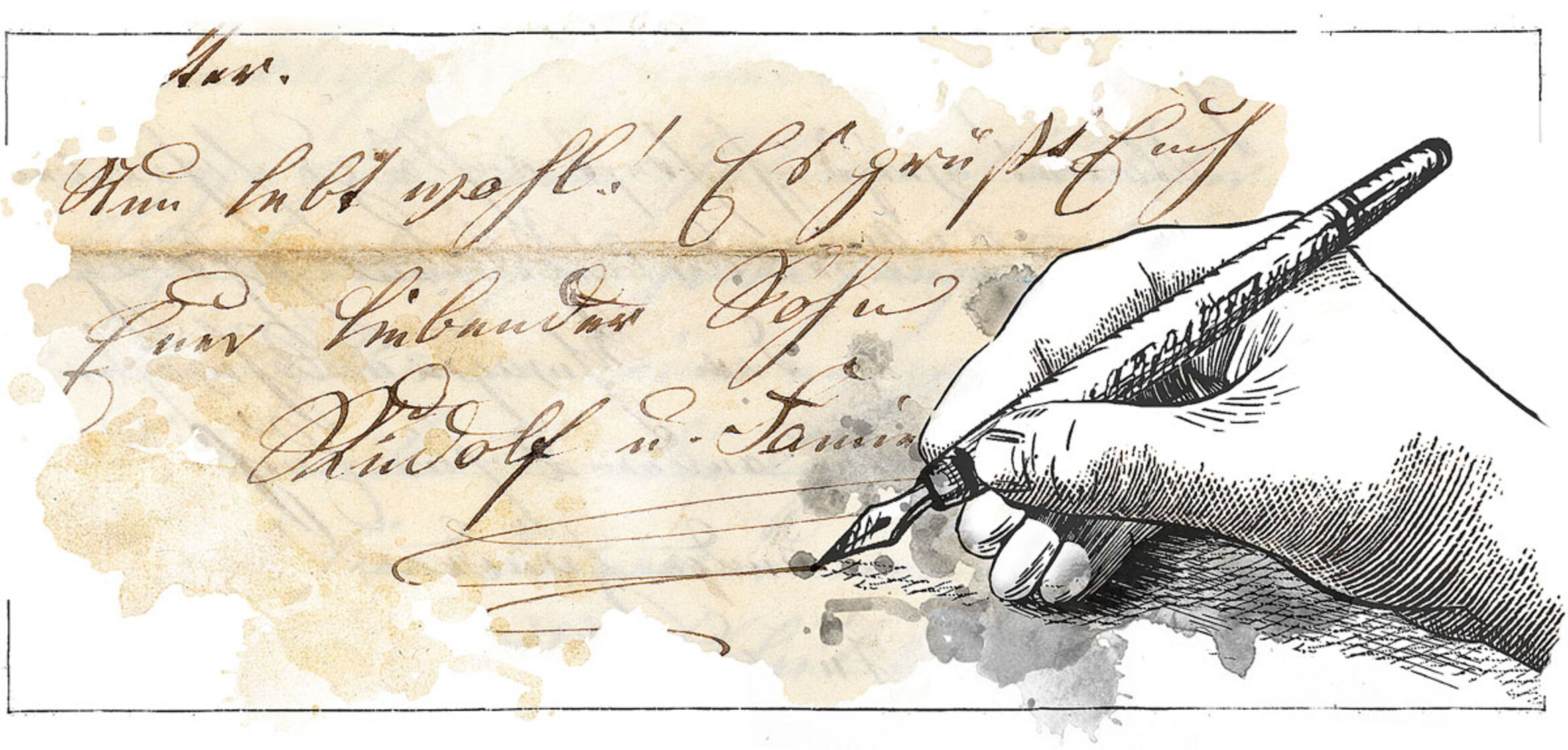

Goodbye, and good luck! The last lines from Rudolph to his mother. It appears to be a conscious farewell. (Illustration by Marco Heer)

Rudolph Heer wrote this fifth and last letter on 16 June 1872. After that, the contact broke off. Reading the last few lines, one is left with the suspicion that this ending was premeditated. In the fourth letter, written at the end of November 1871, Rudolph signed off affectionately, almost effusively:

“Give my regards to David Stüssi and Elsbeth, my brother Samuel and all my siblings, my brother-in-law Jenni and those in Liestal. Live healthily and happily – you only live once after all. Greetings from your loving son and family, Rudolf.”

It was different in June 1872:

“Goodbye, and good luck! Greetings from your loving son Rudolf and family.”

Perhaps contact with his mother reminded Rudolph of how he had failed in Glarus. Perhaps he was embarrassed about his financial situation. Maybe he didn’t want the family to know it was harder in California than “abroad”. But perhaps it was just time for a clean break and an opportunity to start a completely new life in a new home.