City & History | Building transformations

Hürlimann Areal: relaxation in a former brewery

At one point, the Hürlimann brewery in the Zurich district of Enge was the largest brewery in Switzerland. The family business benefited from arrangements within the industry – but when a bigger competitor ultimately bought the operation and shut down, the hops and malt disappeared.

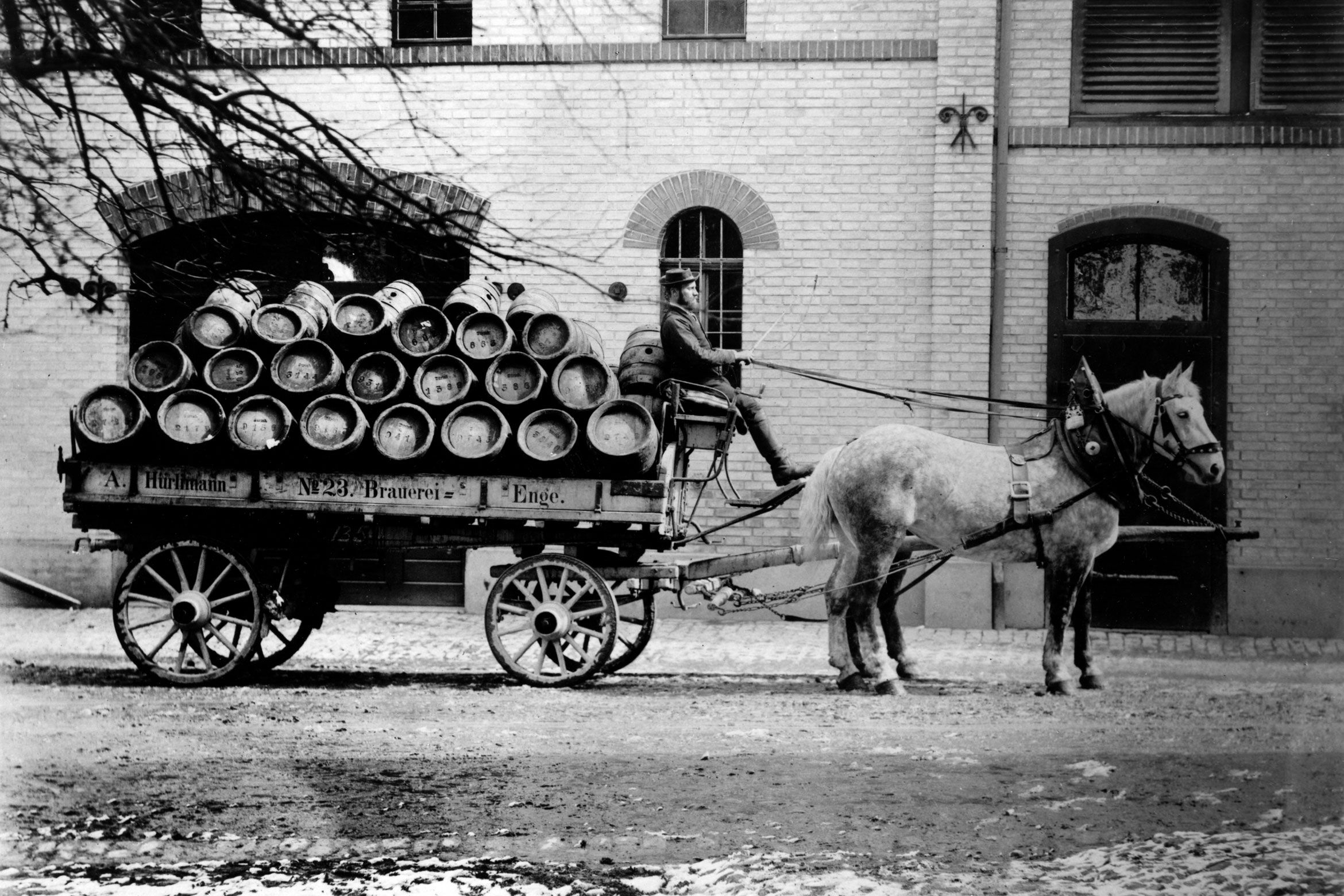

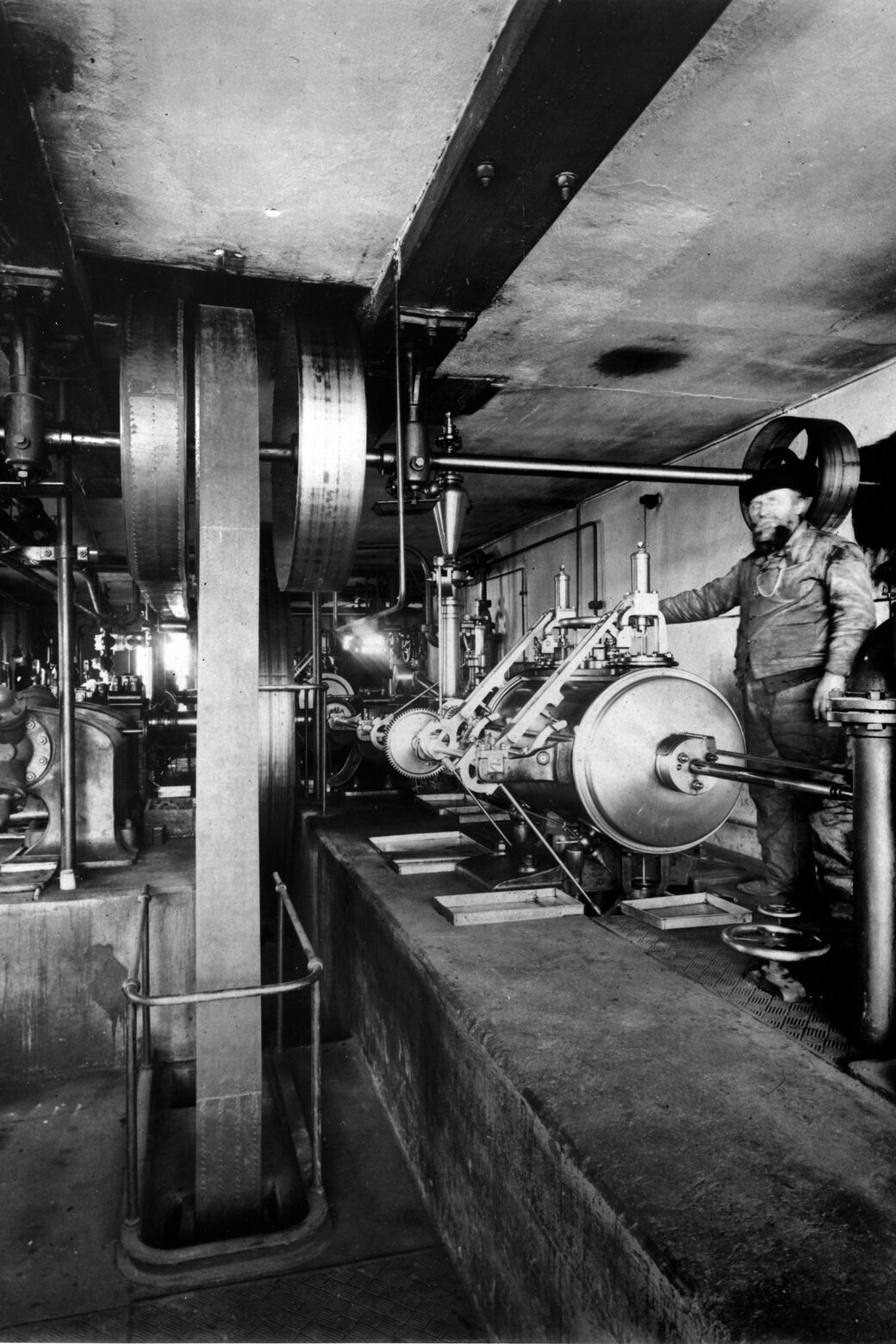

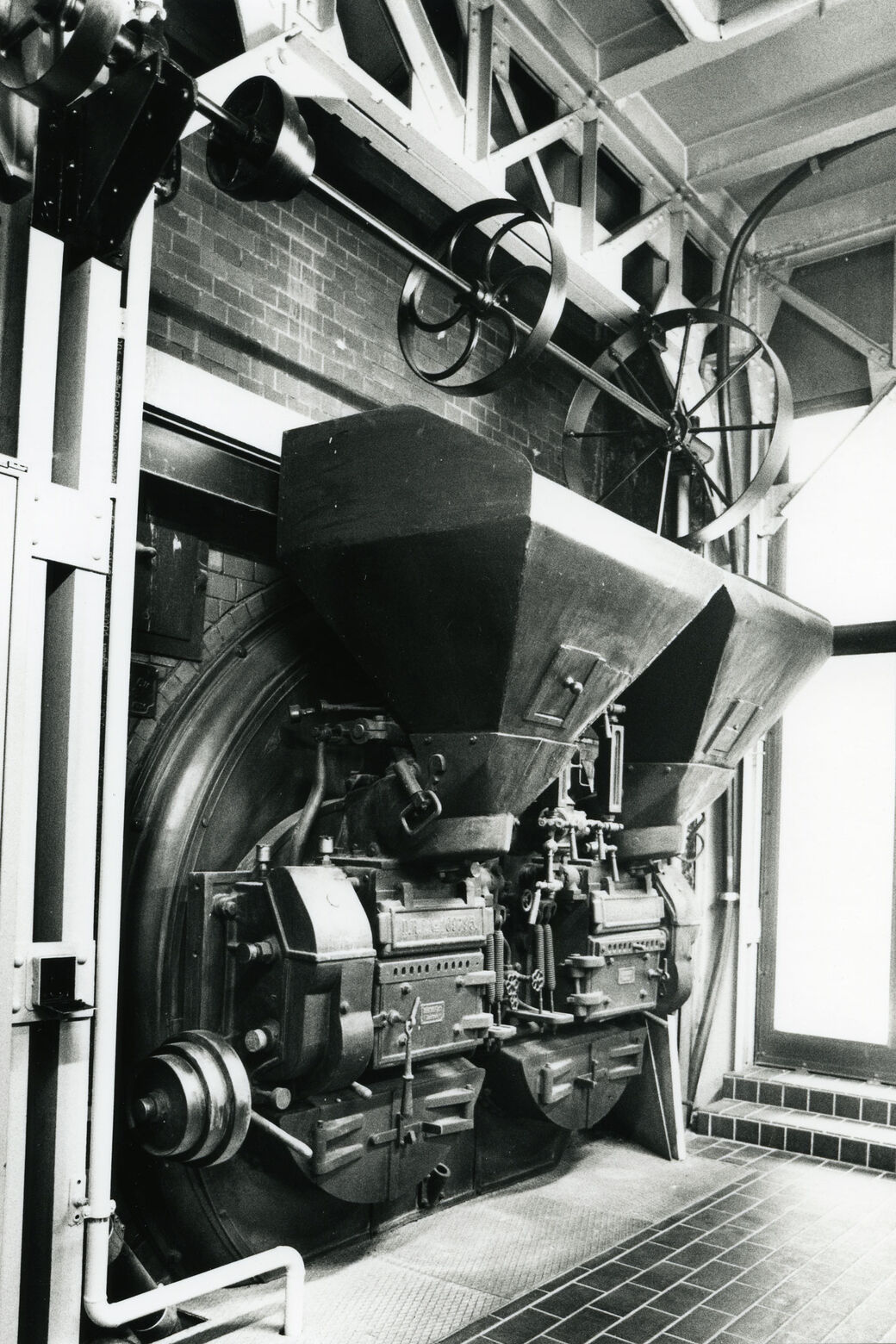

Anyone who mentions beer and Zurich won’t be able to avoid encountering a certain surname: Hürlimann. The site of the former Hürlimann brewery in the Enge area of Zurich was once the centre of industrial brewing in the city on the Limmat. In 1880, it was even the biggest brewery in Switzerland. Today, the Hürlimann Areal is a place of wellness, among other things. In the windowless vaults of the former beer storage area, fans of relaxation now go for a soak in warm water. The large tubs for this are made out of the same material used for the beer barrels: wood.

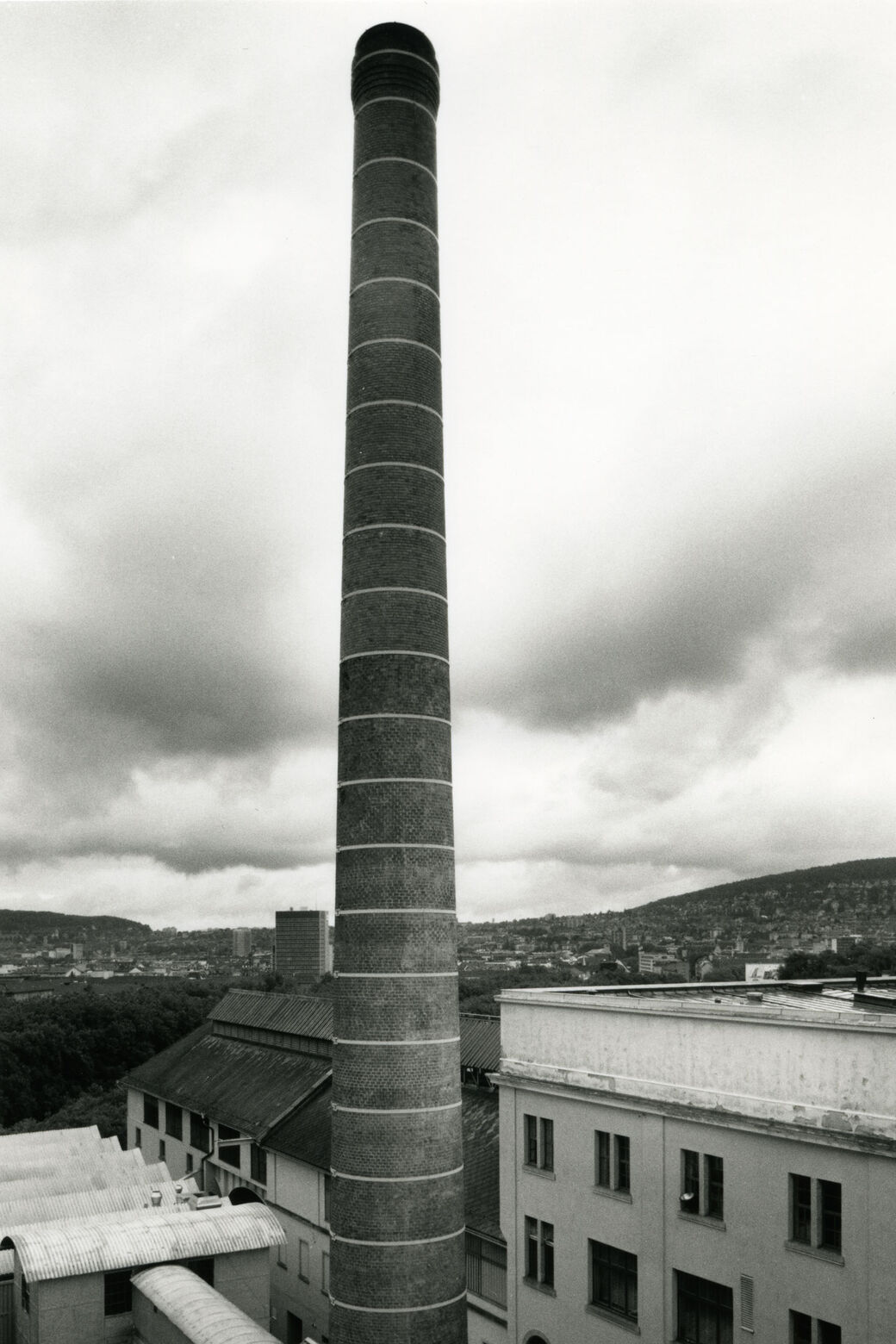

At the Areal, there is now a restaurant and hotel, shops and apartments. In 2008, search engine giant Google also moved its offices to the Hürlimann Areal. In the years that followed, the business continually developed the Zurich location. In 2013, the IT behemoth employed around 1,100 staff, transforming Zurich into Google’s largest research and development location outside the USA. Since then, Google has added further locations in Zurich and now employs around 5,000 Zooglers, as the Zurich employees are referred to in company jargon. However, the Hürlimann Areal’s past as a beer factory is still visible: there’s the characteristic, historic industrial chimney in front of rectangular buildings with exposed bricks. Even the logo of the Areal that appears on façades and at the entrance is still slightly reminiscent of the one with the three beer barrels that is still to be found on the Hürlimann branded bottles and cans to this day.

1836

Hans Heinrich Hürlimann started brewing beer.

The rise to success of the Hürlimann family business started outside the city by the eastern section of Lake Zurich. Heading up the lake a few stops on the S7 train line there is now a station at Feldbach in the municipality of Hombrechtikon. The surrounding area on the upper bank of Lake Zurich has remained idyllic, and it’s here that Hans Heinrich Hürlimann started brewing beer in 1836. In the building on Seestrasse, there is now a restaurant and bar that alludes to its history – for example with beer made by the Hürlimann brand. The lettering on the façade also gives away the fact that the building was once the headquarters of the Hürlimann brewery. The train line hadn’t been built back then, so Hans Heinrich’s son Albert Hürlimann relocated beer production to Enge in 1866 – what was an independent municipality near Zurich at the time already had a train connection. With the first incorporation in 1893, the Hürlimann brewery eventually became part of Zurich.

A beer cartel was formed.

While everything had gone to plan over the previous decades, the mid-1930s marked the beginning of the golden years for Hürlimann. What today might only appear to still be possible in the Grisons construction sector, back then was very much the thing to do in the beer industry: a cartel was formed. The giants of the sector coordinated with each other as part of the Swiss Breweries Association and each took charge of a geographical area, thereby reducing competition and helping to save money. This was possible because the federal constitution of 1874 allowed the formation of cartels. For pub landlords, this meant they had neither the choice nor a selection of beers and had to accept long-term, one-sided contracts. If retailers sold beer from one of the few outside breweries, they faced supplier boycotts. In the meantime, Hürlimann bought up other small breweries around Zurich, shut them down and ultimately became the top dog in the region.

In 1984, Hürlimann absorbed another of the big Zurich breweries, Löwenbräu in what is now district 5 – with ‘absorbed’ meaning buying out and shutting down (1987). In the former Löwenbräu spaces, there are now two art museums. Incidentally, Löwenbräu also had its company roots in Feldbach by Lake Zurich. And there were even more breweries that fell by the wayside or had to close for other reasons as a result of the competition. All that was left, as with the example of the Mühle Tiefenbrunnen, was a building that started off life as a brewery. Where the Dynamo youth cultural centre is today used to be the long-gone Drahtschmiedli brewery.

In 1996, Feldschlösschen took over the Hürlimann brewery.

But towards the end of the 20th century, even the big Swiss industrial breweries also ended up in foreign hands. In 1996, Feldschlösschen took over the Hürlimann brewery, which led to it finally being shut down itself. Since then, Hürlimann has been brewed using Rheinfeld water in Feldschlösschen barrels in Basel. With the takeover of Feldschlösschen by Carlsberg in 2000, the Hürlimann brand then became just a little bit Danish. It almost appears as though the self-inflicted – you might even say communist – tedium of the beer cartel ultimately contributed to its own downfall. At least the beer industry had saved the cost of separately marketing each brand over the years. Instead, they simply advertised as a collective as ‘Swiss beer’ in order to boost sales. However, consumption went down over the years. At the same time, there was a kind of perestroika among pubs, as the cartel had allowed a few foreign speciality beers in the meantime. The thirst for foreign beer was growing.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Hürlimann departed too.

The owner of the Denner discount supermarket, Karl Schweri, played his part in fighting the beer cartel. With his Tell brand of beer and the reference to the mythical hero who didn’t want to bow down to the Gessler reign, he made clever use of Swiss sensitivity on billboards. However, he lost many lawsuits and it’s questionable to what extent he could have contributed to making the beer cartel flinch. Initially, the Cardinal brand from Fribourg was the first cartel member to make an exit, and doing so created resistance within the ranks, the whole Swiss beer Eastern bloc collapsed at the start of the ‘90s, and shortly afterwards Feldschlösschen and Hürlimann departed, too. This allowed many small breweries to spring up, and a similar thing happened in the city of Zurich. For the larger breweries that remained, that meant a large proportion of international brands, until finally all of the big Swiss breweries and beer brands were either owned by the Danish Carlsberg or the Dutch Heineken.

Even if the large breweries have disappeared from the city as industrial enterprises - brewing still takes place in Zurich today. In the case of those microbreweries that belong to a restaurant, this can be seen as a return to the beginnings of Zurich's brewing history: For in the early days, in the 19th century, innkeepers often brewed for their own needs for their own pubs. New brands emerged - their names, Amboss or Turbinenbräu, allude to Zurich's industrial past. Since the early 1990s, one restaurant has been brewing various types of beer on the Steinfels site, a former soap factory. And that, too, is another company story.

Adress

Hürlimann Areal

8002 Zurich