Game, guillotines and gambling

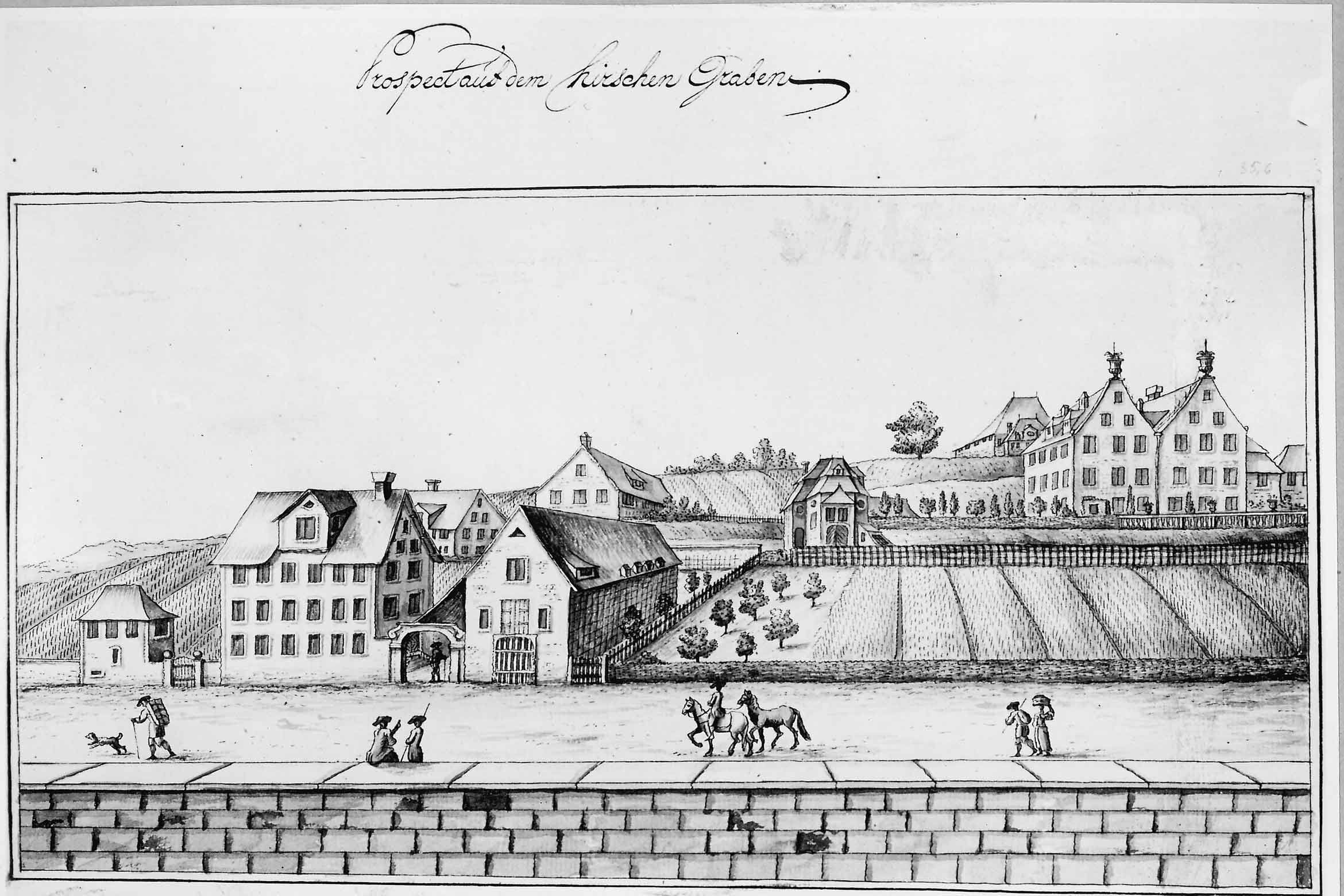

Burggraben, Hirschengraben, Seilergraben. The history of the former defence system is curious. Originally, the moat was supposed to ward off enemies. Then deer grazed in it for two hundred years.

Today, cars and trams thunder past on their way from the Kunsthaus to Central. But a few hundred years ago, the Hirschengraben was exactly what its name suggests. It was a ‘Graben’ – a moat. Several metres deep and wide, the moat – known in the 13th century as the Burggraben zu des Schettelis Turm or Burggraben ze Niumargte – stretched from today’s Central to the junction of Torgasse and Oberdorfstrasse. Located beneath the eastern city walls, it was designed to keep unwelcome visitors at bay. The moat was first mentioned in 1335 in connection with an extension of the marketplace.

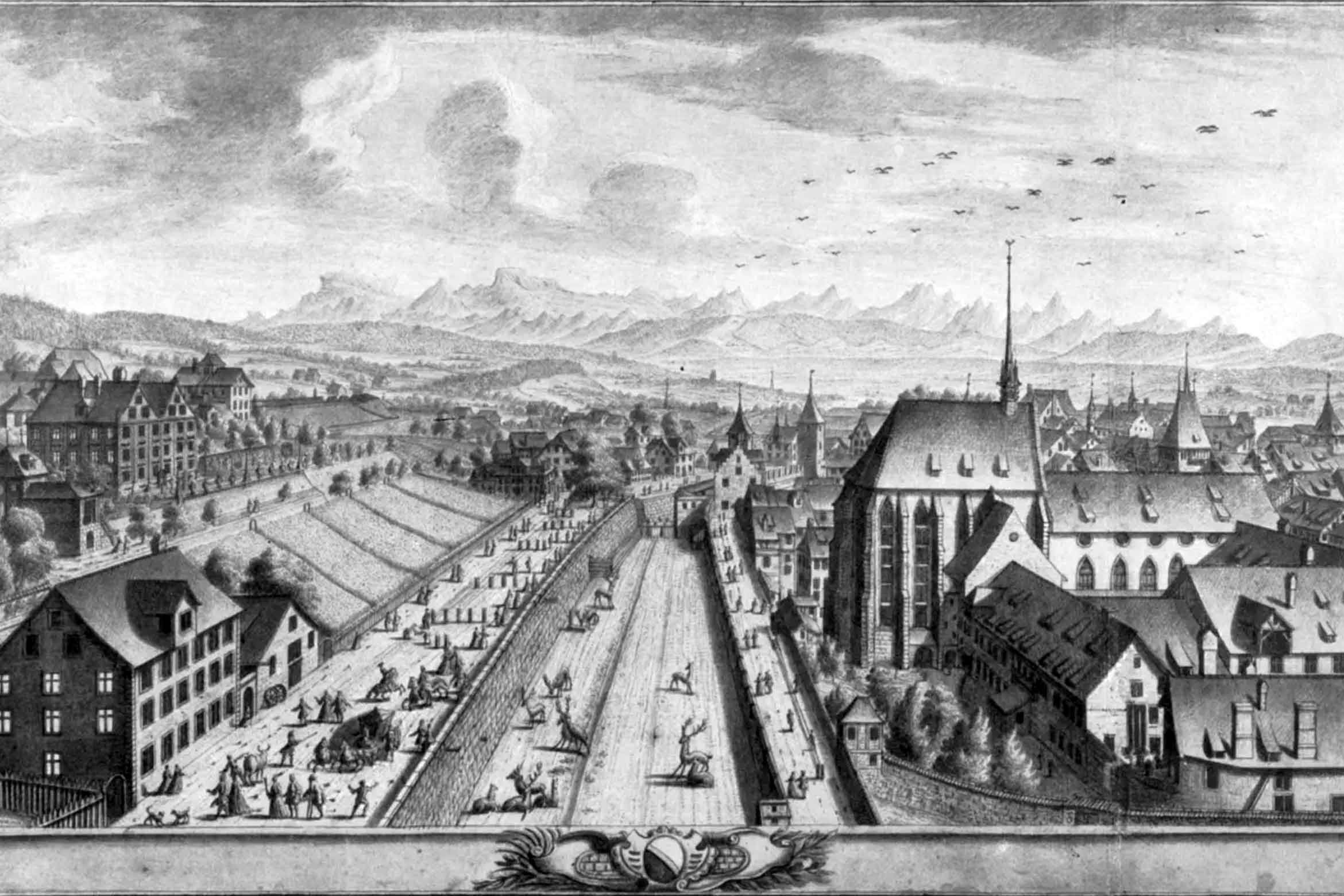

Deer grazed in the city for two hundred years.

As Zurich expanded over the years and more and more people moved in, the council had to limit the number of cattle that were allowed to graze within the city limits. It became increasingly rare to see cows, pigs, sheep and chickens in the city’s green moats, and in 1527 they were finally banished to the fields outside the city gates. But now the question was: what should we do with the city moat? It was decided to replace the domestic animals with dozens of deer.

The first written record of hunting game in the city moat dates back to 1529. Gamekeepers fed the animals and cleaned the moats. The grazing deer attracted visitors and onlookers, and as the centuries went by the city moat became known as the Hirschengraben – the deer moat, a name that it bears to this day.

Many deer were killed in a fire.

On 13 September 1744, one of the deer shelters was burnt to the ground. It is said that a youth called Beat Froschauer set it alight during morning service. It is unclear whether this was an accident or intentional, but we do have a written record of Froschauer’s punishment – the young man was summarily beheaded for causing the fire, which killed several deer. The shelter was rebuilt, and the deer were allowed to continue grazing in the moat until 1774, when they finally had to make way for the city council’s new plans.

Parts of the Hirschengraben were given a new name.

Certain sections of the Hirschengraben were levelled in 1780. This created a new area stretching from Niederdorf to the Neumarkttor, which went to the ropemakers’ guild. They opened up their shops and warehouses and offered their goods and services. This is how the outer and upper part of the moat kept the name Hirschengraben, while the inner and lower part was gradually given a new name: Seilergraben (ropemakers’ moat).

For many years, the Seilergraben was mainly used for work and commerce, while the Hirschengraben was a more pleasant place to while away the time. The circular rampart and the towers known as the Wolfturm or Schrätteliturm were pulled down in 1790. The rubble and stones were used to fill in and level large sections of the former moat. This created a green promenade and avenue leading from the Kronentor at Neumarkt to the Lindentor at the entrance to Kirchgasse. Fairs, parades and festivals were held in the Hirschengraben until the end of the 18th century. During the 19th century, the sides were built up with solid stone retaining walls so that it could also be used by larger vehicles.

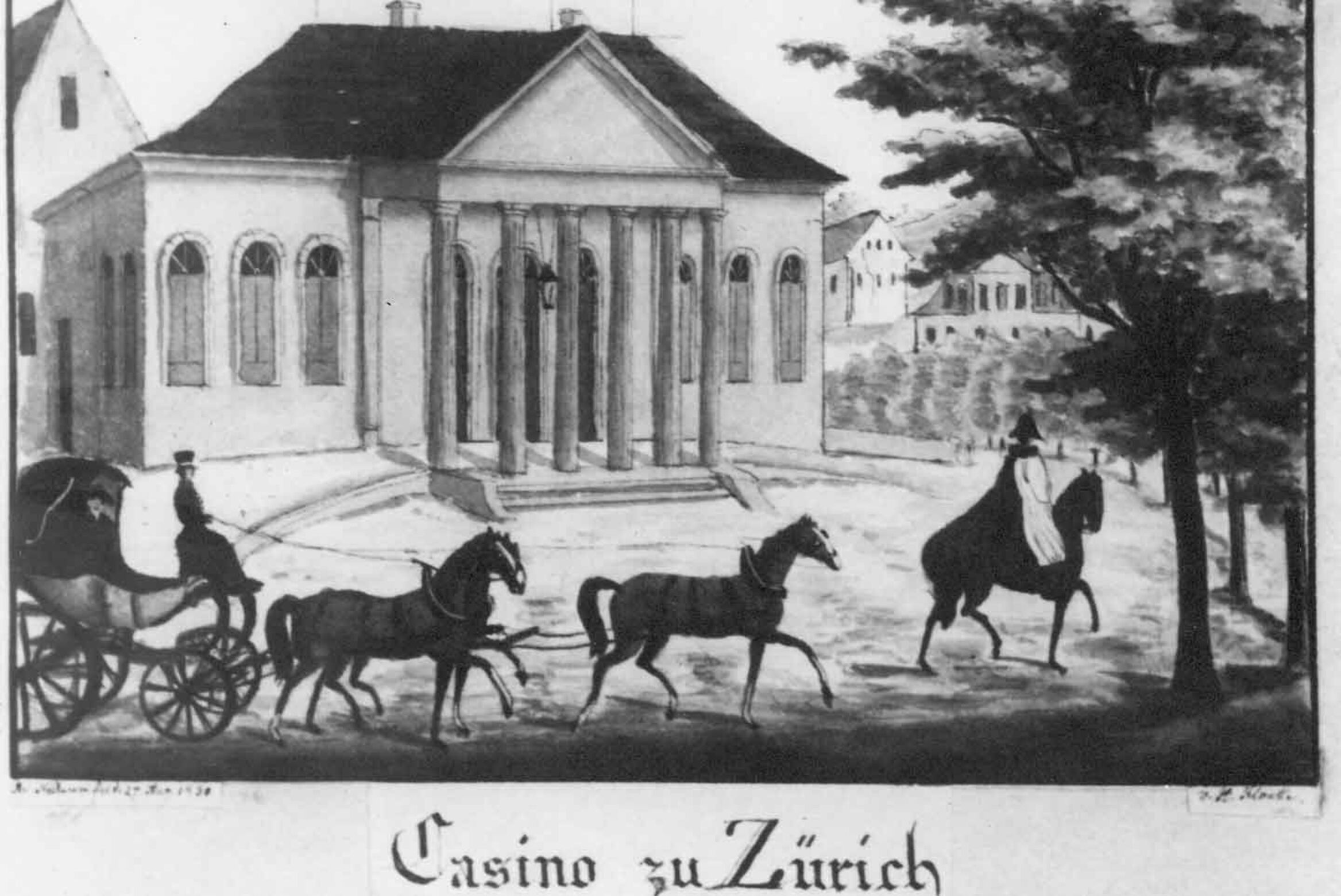

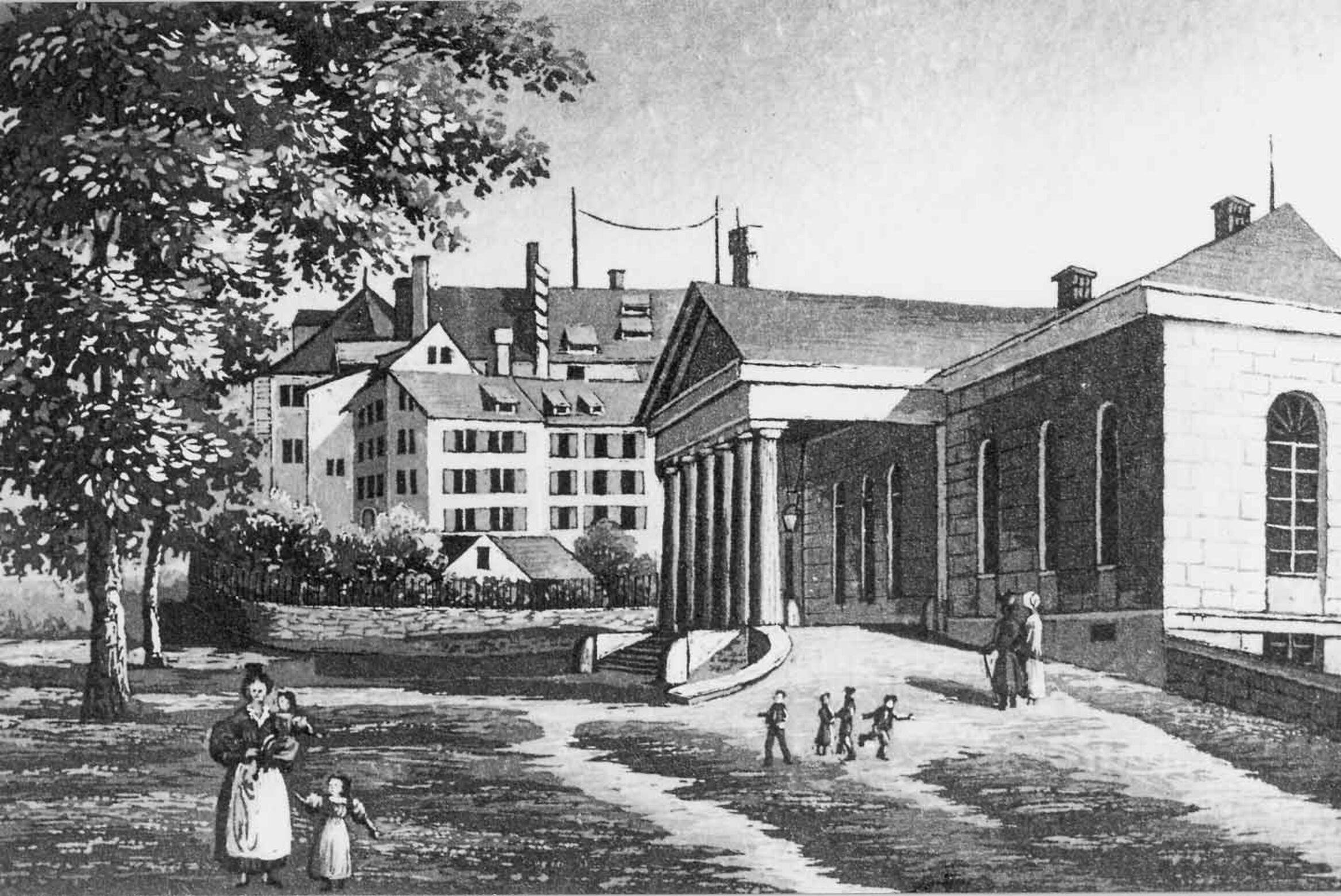

A casino opens on Hirschengraben.

In 1806, the Assemblee Society acquired part of the former Barfüsserkloster, a Franciscan abbey that had stood on the upper Hirschengraben since 1283. This section was partially demolished and rebuilt in strict Classical style at a cost of 40,000 francs. It was turned into something that was far removed from the former monastery: a casino. The people of Zurich could try their luck there for almost 70 years.

When the German writer, physician and revolutionary Georg Büchner was staying in Zurich in 1837, he wrote to his fiancée: ‘Every evening I spend one or two hours in the casino. You know how much I love beautiful rooms, lights and people around me.’ In 1874, the city bought back the casino and once again gave it a whole new use as the city’s high court, which still stands on Hirschengraben today.