Flirty Tennis

Seeing and being seen is an important social aspect of sport. At one time, this was a particularly notable feature of tennis.

Imagine Martina Hingis and Roger Federer meeting for a tennis match with the intention of hitting a few rallies, and having a flirt and a bit of on-court courting. A preposterous idea? In today’s terms, yes, but if the two Swiss tennis aces had lived 150 years ago, that would have been completely normal. In the early days of modern tennis from 1870 onwards, the game was not considered a competitive sport, but an entertaining upper-class diversion, in which the balls were merely patted back and forth in a relaxed manner. In these circles, it was good manners for a young lady or a young man to play tennis.

A certain level of separation from the ‘common people’ has always been important.

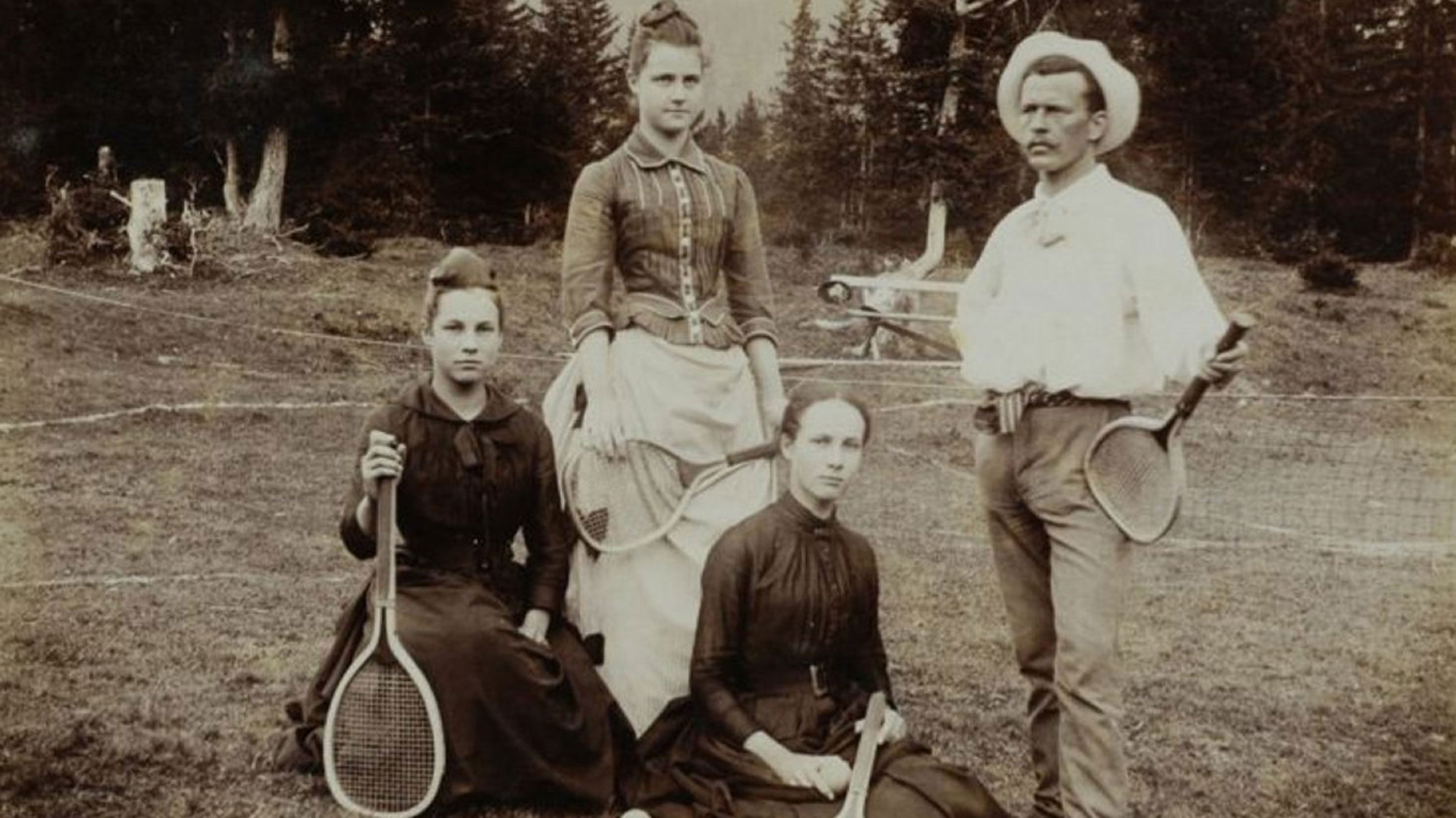

Tennis in Prangins, late 19th century.

This type of tennis was developed in England under the name lawn tennis, and was derived from pre modern archetypes such as Jeu de Paume, which was played predominantly by the French and English nobility in monasteries and indoor ball courts. A certain level of separation from the ‘common people’ has always been important. In spatial terms this distance has been maintained through the indoor ball courts mostly built by members of the aristocracy, and later, among the middle classes, by means of exclusive clubs; externally, the distinguishing feature was the wearing of fashions befitting the player’s social standing. The gentlemen wore long trousers, long-sleeved shirts and peaked caps, while the ladies played in voluminous corsetted garments which, in accordance with the moral ideas of the time, were required to cover every inch of skin. In such attire, there was no possibility of being ‘competitive’.

Jeu de Paume in Paris, 17th century.

Not only the game of tennis itself, but also the associated class consciousness was imported from England and copied.

Like many other sports, tennis found its way to Switzerland through English tourists around 1880. There was an indoor ball court dating from the early modern era in Basel, but the first documented mention of tennis players in this country dates from 1883, when well-bred gentlemen from England are said to have played tennis in Montreux. From the Lake Geneva region the game then spread throughout Switzerland, with our own upper crust taking to the new game early on.

In 1883 the Club anglais de Lawn Tennis was founded by Swiss and English enthusiasts in Lausanne, and soon after that clubs were set up in Basel, Bern, Montreux, Zurich, Bad Ragaz, Engelberg and Lucerne – all places that had links with Great Britain via tourism or business relations and typified a certain exclusivity. So not only the game of tennis itself, but also the associated class consciousness was imported from England and copied.

The imageof a “modern-day institution of betrothal”.

According to an anniversary publication issued by the Schweizerische Tennisverband dating from 1936, tennis was popular among the upper classes also because “it offered both sexes the opportunity to engage in exercise together; in addition, it required greater use of physical strength and in particular it appealed much more strongly than did the somewhat stiff game with the wooden ball [meaning croquet] to the recently awakened impulse to be active felt by young people”. Athletic exertion was thus very much part of the programme, but even 30 years after its emergence tennis still hadn’t managed to shake off the image, favoured by the population at large, of a “wimpish type of game unbefitting a healthy body” and a “modern-day institution of betrothal”. The game was a “sport of flirtation [...], completely devoid of any masculine character whatsoever. [...] If you showed your face in the street in your tennis outfit, you were gawked at or at the very least quietly mocked as having a hidden agenda, you were on your way to some flirtation or assignation. [...] ‘Wenn es Maitli kei Ma find’t, fangt sie a, Balle umenand spicke’.”

Zurich tennis player from 1917.

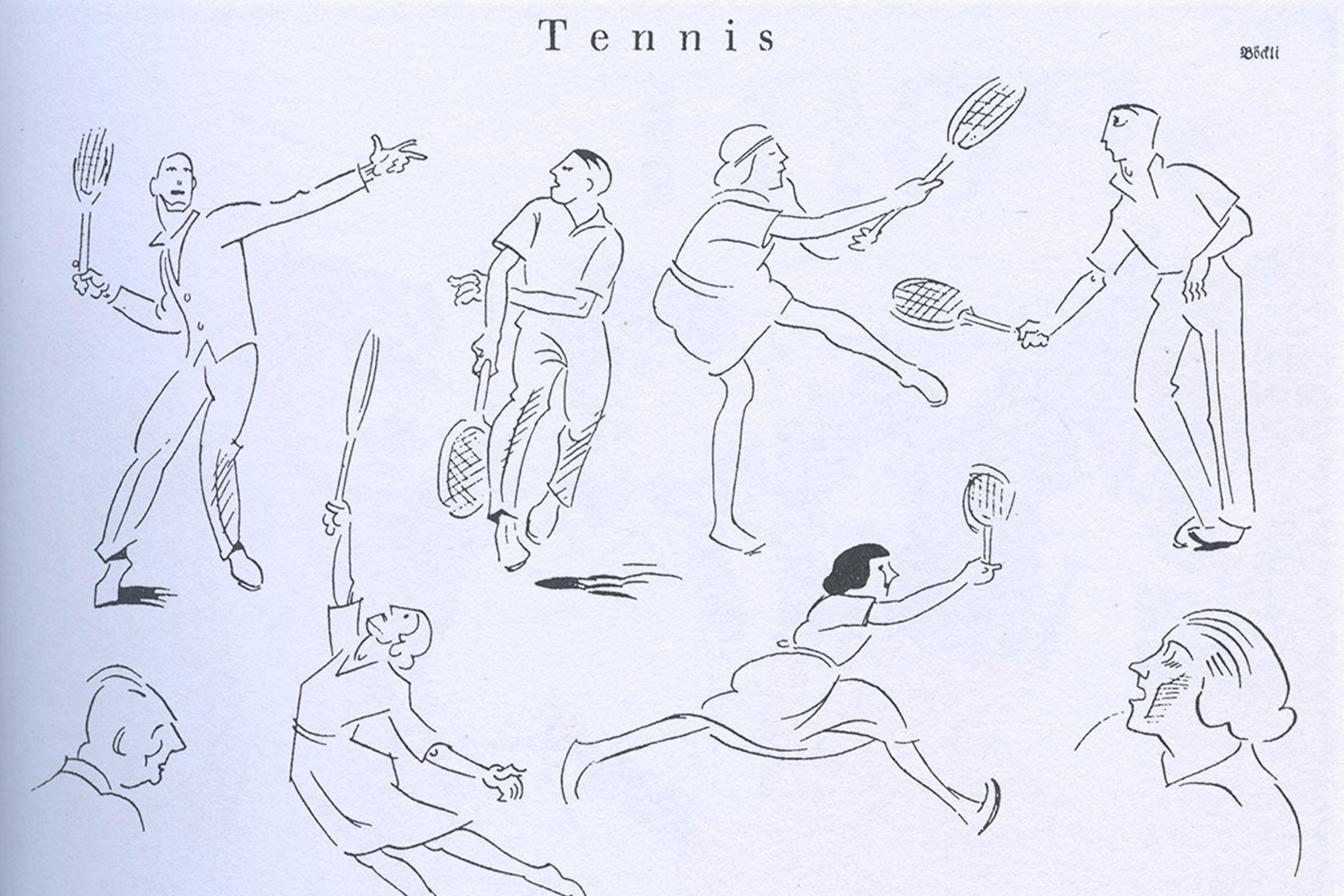

The fashions, the equipment and the specific movements of tennis play were also cause for ridicule: in Lucerne, for instance, locals are said to have referred to the tennis courts as monkey cages, where balls were passed back and forth from one player to another, and we have on record one sportsperson’s recollection of the first tennis court in the city of Bern, in 1890: “The ladies with their billowing mourning veils, laced bodices and long, heavily pleated skirts, their squires with waxed moustaches, walking canes and carnations in their buttonholes must have stared askance at the first five members as they scampered about on the grass court levelled out with sand, chasing a white ball, with indecent contortions of their limbs and a strange implement, a cross between a fly swat and a ladies’ fan.”

Not a game of brute strength with physical contact, but a “sport of beauty in movement”.

Caricature in the Nebelspalter from 1925, poking fun at the peculiar movements of tennis players.

Although the game was regarded by most as silly or wimpish, at the turn of the century tennis was one of the few opportunities for women to play sport, precisely because it fitted with the prevailing perceptions of the female body ideal. Contemporary sources report that tennis was not a game of brute strength with physical contact, but a “sport of beauty in movement”, a game of “dexterity and agility” and enabled players to “give perfect expression to the natural grace and suppleness of the body in motion”. As far as possible, the game was to entail no physical exertion; when a woman played against a man, it was therefore expected that the man would play the balls in such a way that, at all times, the gentlewoman could hit them back. Anything else would have been ‘improper’. As such, the rackets were very loosely strung by today’s standards, to ensure the returns didn’t come back fast and hard.

Caricature on the flirtatious sport of tennis in the Nebelspalter, 1888.

The image of the exclusive “white sport” has to some extent remained.

By the immediate post-World War I period tennis had broken away from the image of the amusing recreational activity, and began to develop into the strength and endurance sport as we know it today, also percolating down to less affluent classes of society. Commercialisation and professionalisation went hand in hand. However, depending on the location and tradition, the image of the exclusive “white sport” has to some extent remained; for instance, the tournament at Wimbledon, home of lawn tennis, still eschews the use of perimeter advertising, and stipulates white clothing for players. But whether the tennis professionals still meet up away from the cameras for a ‘traditional’ tennis flirtation, only the English tabloid press knows.