Gull’s big break

Gustav Gull’s design for the Swiss National Museum in the late 19th century marked the start of his rise to become a star architect.

In 1898, Gustav Gull (1858–1942) was Zurich’s best-known and most influential architect. By designing the Swiss National Museum, he had realised a major building of national importance and international standing. Meanwhile, as municipal architect he embarked on the design of the current city hall. His work on the National Museum in 1890 laid the foundations for a glittering architectural career.

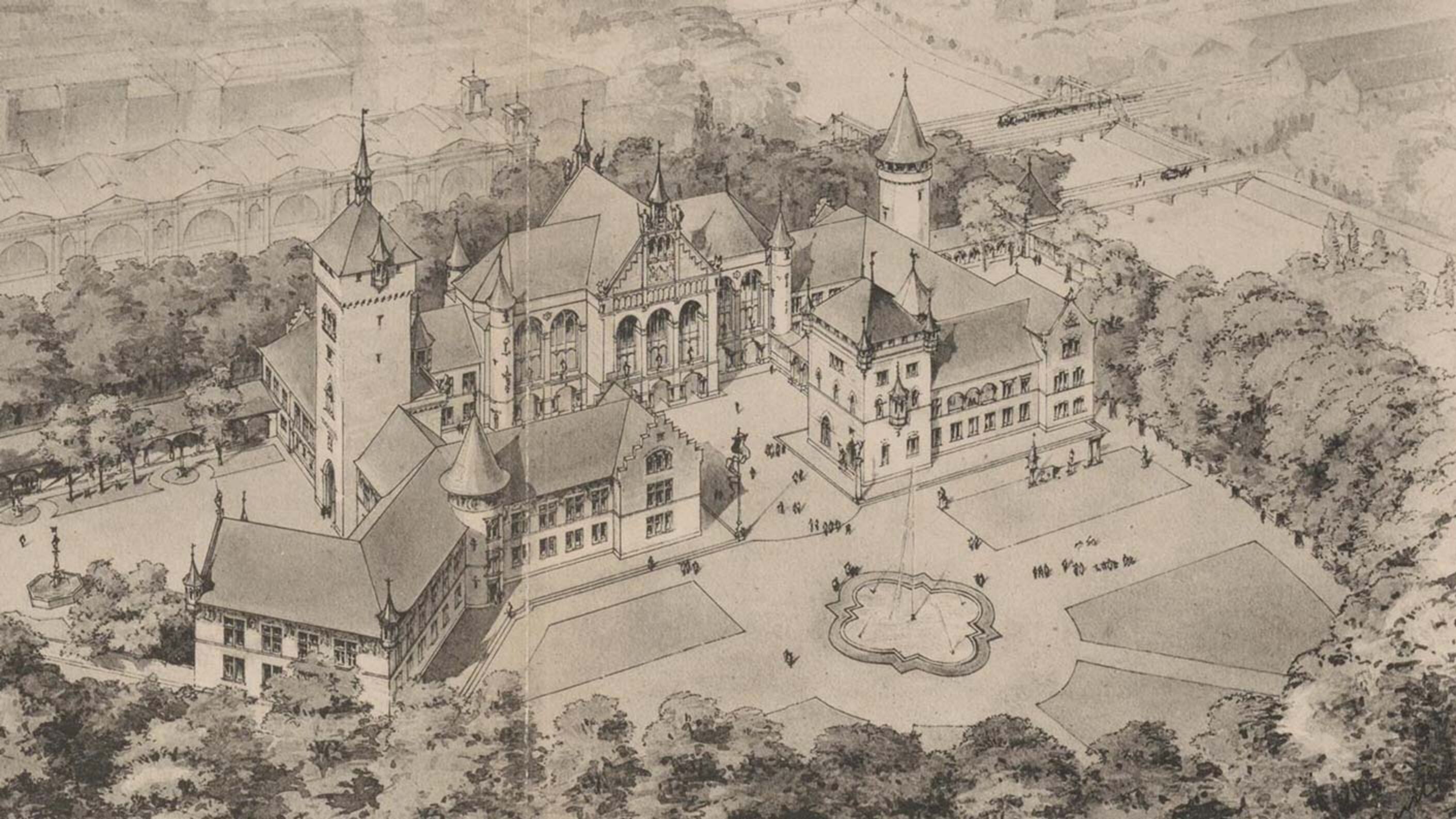

With drawings like this one, Gustav Gull was able to win over all involved with ‘his’ vision for the National Museum. Swiss National Museum

It was by chance that Gull was given the unique opportunity to produce the design for Zurich’s application to host the museum. Shortly before the submission deadline, the committee for a national museum in Zurich still didn’t have a plan for the museum building. The city had provided an outstanding site on the peninsula between the Limmat and Sihl rivers, which is where the industrial hall from the Swiss National Exhibition of 1883 had stood.

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

An important element for those campaigning for the National Museum to be located in Zurich were the period rooms. Johann Rudolf Rahn, the influential art historian from Zurich, had recognised the handcrafts contained in the Swiss period rooms as a specifically Swiss art form. He thus shaped the acquisition policy of the future National Museum. While not wanting to pre-empt the creation of a national museum, the federal government had acquired a number of period rooms dating from the 15th to the 17th centuries. In its application to host the new national museum, Zurich therefore also offered the famous state rooms from the Alte Seidenhof and two abbess rooms from the former Fraumünster convent.

This ink pen drawing shows the museum courtyard with a view of the gate tower. The image was part of Zurich’s application to host the new national museum. Swiss National Museum

Depiction of the small abbess room in Zurich’s application, drawn and signed by Hermann Fietz. Swiss National Museum

The advocates of a national museum in Zurich did not just want a ‘box’ to house the museum, but a building that was in keeping with the period rooms. However, two renowned architects – Alfred Friedrich Bluntschli and Albert Müller – declined the offer to collaborate on the project. As representatives of the neo-Renaissance influenced by Gottfried Semper, perhaps they felt that they would never be able to satisfy the vague architectural ideas of the committee. The young architect Hermann Fietz, who was probably put forward by Friedrich Bluntschli and Johann Rudolf Rahn, then suggested working with Gustav Gull. Gull had realised the federal post office building in Lucerne between 1886 and 1888 but had yet to replicate that success in Zurich.

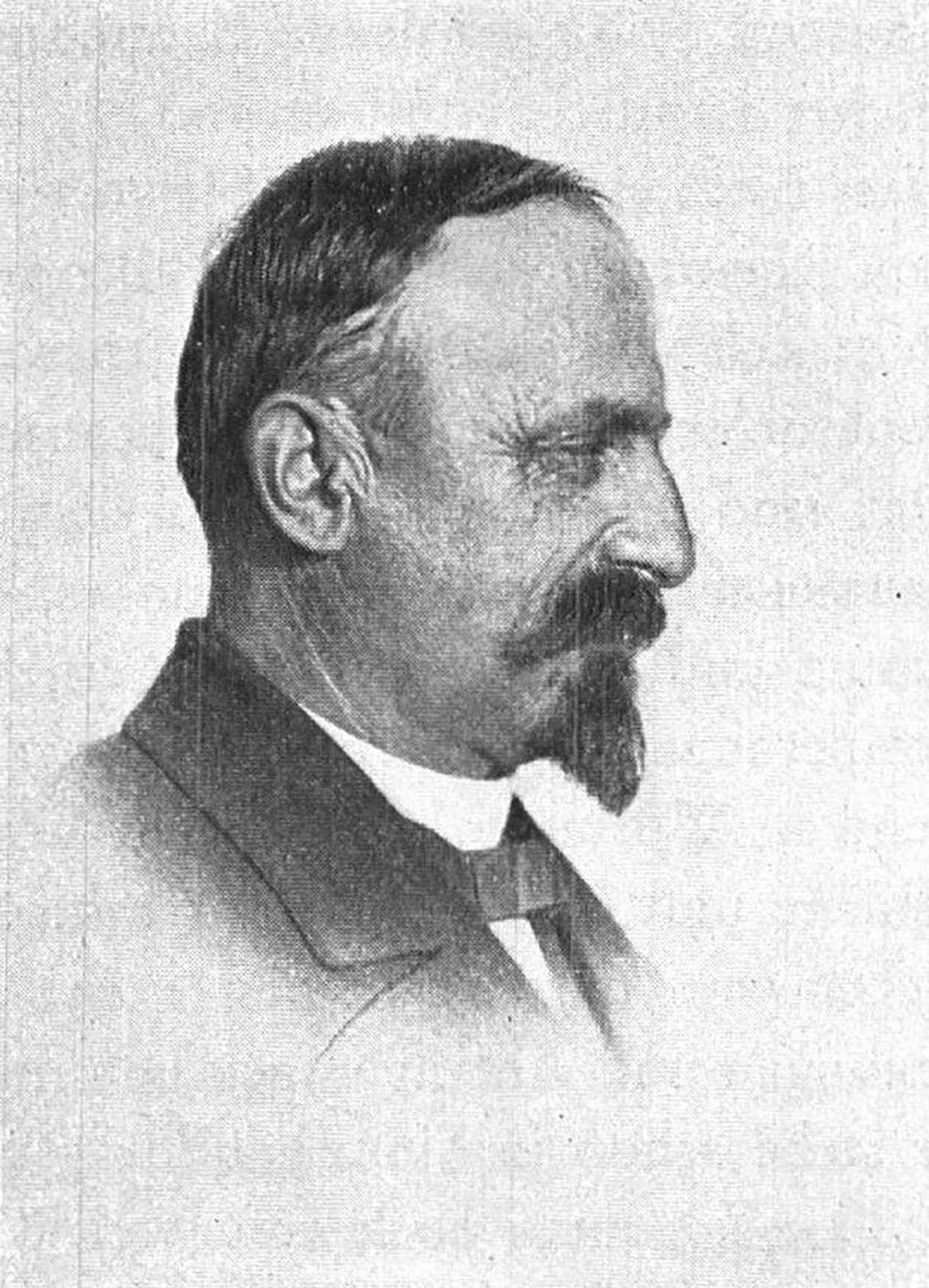

Hermann Fietz was Zurich cantonal architect for over 30 years. e-periodica

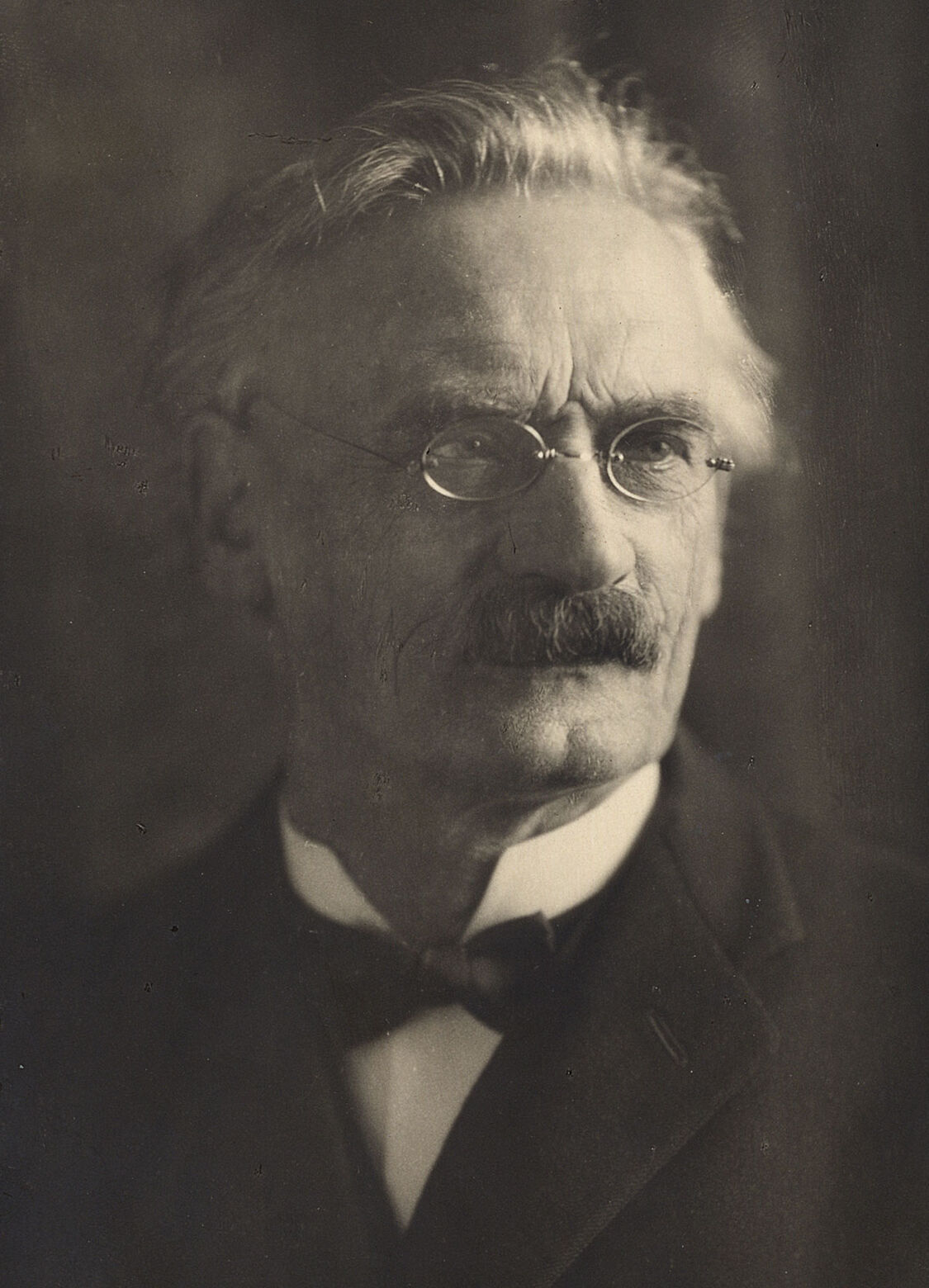

Gustav Gull in the 1930s. ETH Library Zurich

Gull jumped at the unique opportunity. In a short space of time, the two architects developed a novel museum design. On the drawings, Gull emphasised his role as author. Fietz stepped aside and gave his older colleague free rein and soon withdrew from the project altogether so he could dedicate himself to his own commissions and work in Friedrich Bluntschli’s office. Gull did not design a symmetrical monument building, but a conglomeration which organically incorporated the original architectural elements. In so doing, he drew on the transitional style from the period between late Gothic and Renaissance in Switzerland. The fact that he was able to break with the Semper tradition was thanks in no small part to Johann Rudolf Rahn, who was the first to produce an overview of Swiss art history, from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Thanks to Gull’s museum design, Zurich’s application was a resounding success. This is also evident from the fact that the city of Bern withdrew its museum project during the selection procedure, opting to replace it with a plan that picked up on the architectural elements of Gull’s design – and would later become the Bern Historical Museum.

The Bern Historical Museum on a photo taken between 1896 and 1900. Burgerbibliothek Bern

In 1895, while the museum was still being built, Gull became Zurich’s second municipal architect – a position with a great deal of power. The incorporation of eleven suburbs in 1893 had made Zurich Switzerland’s biggest city, and it wanted new administrative buildings to reflect its new-found status. In his design for the National Museum, Gull successfully developed an architecture that represented a historical awareness but with a link to the present. The mayor of Zurich, Hans Pestalozzi, who was a member of the committee pushing for Zurich to host the new national museum, was excited by Gull’s design skills. Gull was therefore the ideal candidate for the position of second city architect. However, the decision to award him the position, despite the slow progress of the work on the National Museum, led to considerable conflicts between the municipal and museum authorities. The city therefore decided to put the municipal administrative building project on hold until the National Museum was complete. During the building phase, Gustav Gull only designed the schoolhouse on Lavaterstrasse for which he took inspiration from the architectural style of the National Museum. In doing so, he fully satisfied the expectations of his role as municipal architect.

The Lavater school building in Zurich. Building history archive

As the architect behind the National Museum, Gull advocated conserving the historic monuments and reviving the original architectural elements in the museum. In parallel, in his role as municipal architect, he transformed two historically challenging sites on which medieval buildings stood. The rooms from the former Fraumünster convent in the National Museum reflect the tension between conservation and renovation that shaped Gull’s work while he was both architect of the National Museum and municipal architect because the convent buildings were being demolished just as the Museum was officially opened on 25 June 1898. In the subsequent construction of the city hall, Gull successfully connected his design to that of the National Museum and included an architectural nod to the lost architecture of the demolished convent. When he left his position as second municipal architect to take up a professorship at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich in 1900, there was no doubt that the city would entrust him with the planned construction of municipal buildings on the site of the former convent in Oetenbach, which had been started in late 1897. It was the most important and largest commission of the city of Zurich at the time and paved the way for the city’s current official buildings.

Zurich city hall designed by Gull on the site of the former Fraumünster convent. Photo circa 1915. ETH Library Zurich