Hansli disappears in the heart of Altstetten

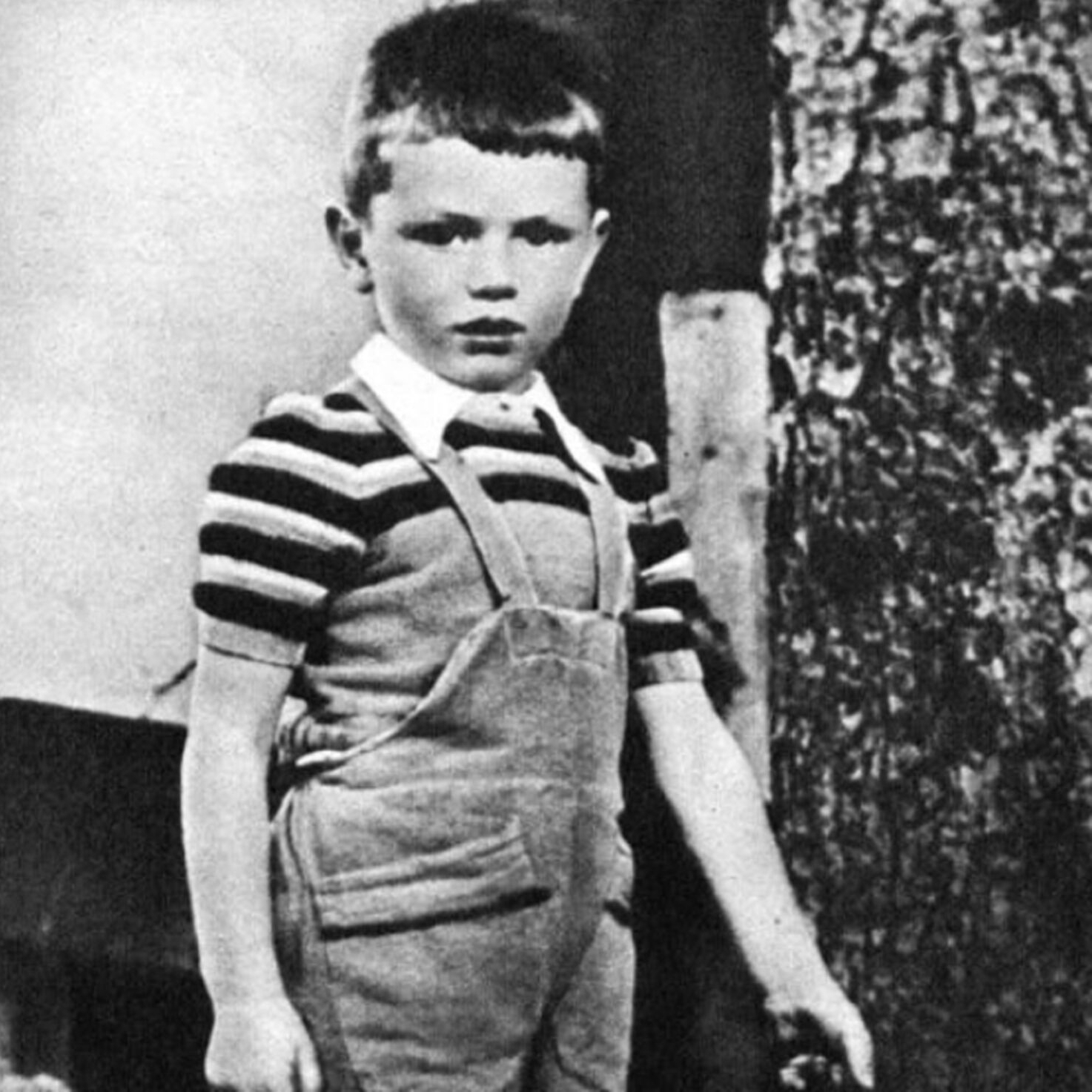

In 1949, Zurich was in uproar over the case of a missing boy. 5-year-old Hansli Eichenberger walked round the corner to buy some lemons at Migros and never returned. His case tied up hundreds of police officers, drove a man insane – and inspired Friedrich Dürrenmatt to write It Happened in Broad Daylight.

It’s just before midday on 20 May 1949. Hansli Eichenberger’s mother sends her 5-year-old son to the local Migros store to buy a kilo of lemons. Later on, a store assistant remembers serving the boy. But he never comes home. At 1.50 pm, Hansli’s father reports him missing.

The following afternoon, the Zurich police find Hansli’s shopping bag stuffed into a concrete pipe. It contains the boy’s underpants and a handkerchief, both spattered with blood. Later on, the police decide the blood on the handkerchief is irrelevant, probably just the result of a harmless nosebleed. The newspapers report how the police have examined the items using the ‘latest microbiological methods’ – but it is all in vain.

The police scour garages, warehouses and chimneys.

Altstetten around 1949. (Photo: Wolf-Bender Heinrich & Wolf Bender's Erben)

Over the next few days, officers comb the area around Hansli’s home on Vulkanstrasse in Zurich-Altstetten. In its 25 January 1950 edition, the Schweizer Illustrierte describes it as ‘a massive search operation.’ The police scour garages, warehouses, chimneys and sewers, empty factory drainage systems and use special equipment to search the River Limmat. A leaflet is circulated to property owners and allotment holders asking them to keep an eye out. Farmers are encouraged to check their dung heaps and cess pits. Dry cleaners are told that any suspicious blood stains should be immediately reported to the police.

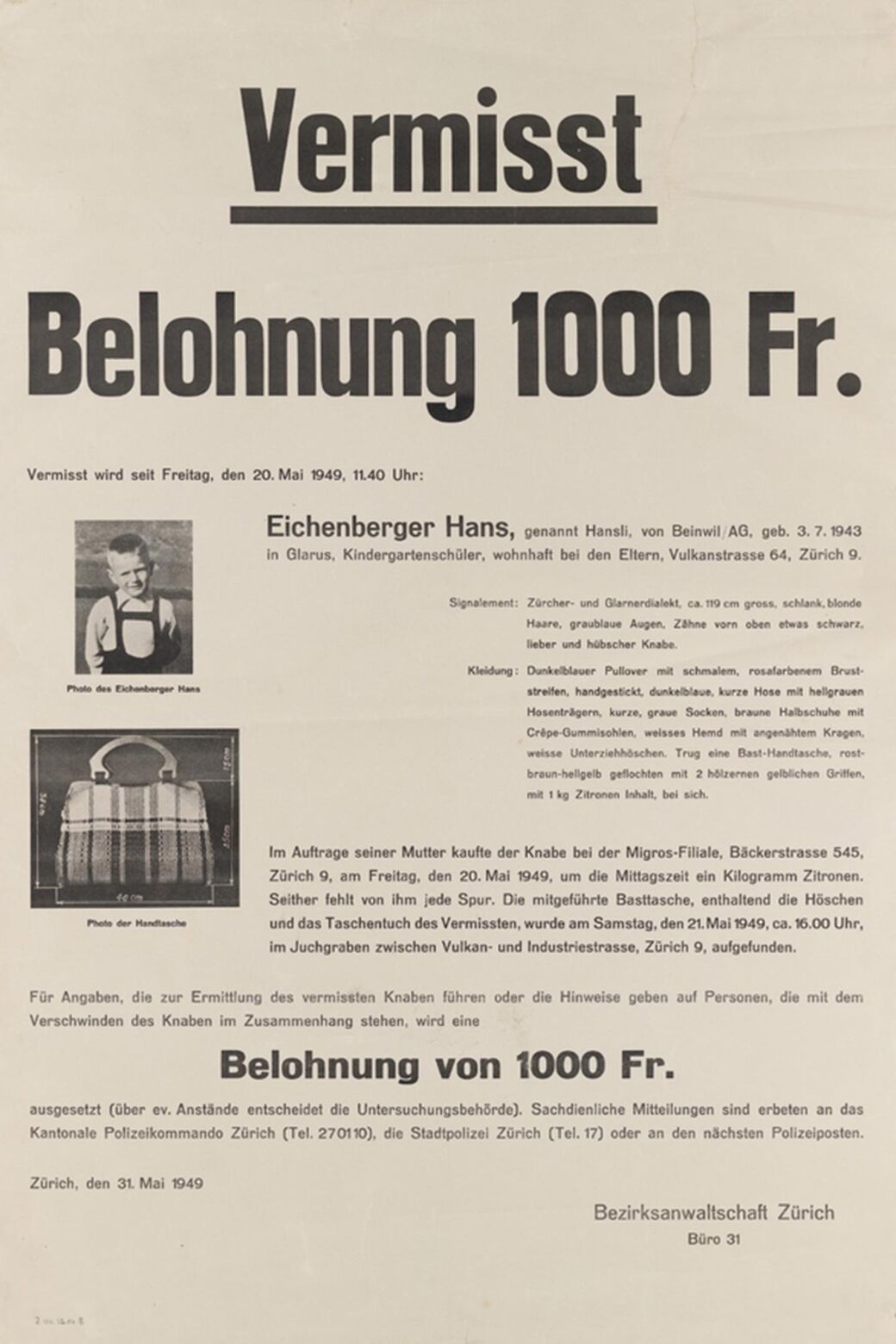

Ten days after Hansli’s disappearance, the district attorney’s office puts up posters saying ‘Missing – 1,000-franc reward’. They bear a picture of Hansli and describe him as ‘a sweet, handsome boy’.

The district attorney’s office puts up posters saying ‘Missing – 1,000-franc reward’.

(Photo: Staatsarchiv Zürich)

In desperation, Hansli’s family seeks the help of foreign psychics, including Cordon Veri from Vienna, who has officially offered his services to the police. A newspaper photo shows him swinging a pendulum in the Eichenbergers’ living room. Other clairvoyants try a variety of means to locate the child’s body, some using divining rods, others ordinary handkerchiefs.

The police receive more than a thousand tip-offs from the public and follow up on each one, a process that can take up to five days. Hundreds of men work up to 16 hours a day on the case – including Sundays.

By 1950, the police had invested 12,000 man-hours in the case.

One witness reports seeing a strange man looking into a concrete pipe then driving off in a dark blue car. The story is confirmed by another witness, but the description of the suspect is vague: a man, medium build, 30 to 40 years old. The police check more than 800 cars in the canton of Zurich alone. Years later, people still recount things that people claimed to have seen, such as Hansli desperately waving for help from the rear window of the blue car.

After Hansli’s disappearance, the police kept a close eye on suicides throughout Switzerland and required nearly a thousand people with criminal records to provide an alibi for the time of the crime.

The people of Zurich were also not ready to give up on the ‘Hansli’ case.

The police also followed up on leads in other countries. A child’s corpse was pulled from the River Po in Italy, and a Cologne radio station reported on a ‘Hansli’ who was looking for his mother – but neither of them was the missing boy from Zurich.

By 1950, the police had invested 12,000 man-hours in the case but continued to follow up on leads. The people of Zurich were also not ready to give up on the ‘Hansli’ case. One man was so obsessed by it that he lost his mind and was committed to the Burghölzli mental asylum. Another woman from Zurich came close to the same fate.

Despite all their efforts, the police found neither the perpetrator nor Hansli’s body. The last piece of hard evidence was the six lemons that were found in a nearby field 14 days after the boy disappeared.

The police provided Dürrenmatt with information about a similar case.

The film producer Lazar Wechsler also heard about Hansli’s disappearance. Shortly before the incident, the weekly magazine Weltwoche had asked him about some rather tame films, saying: ‘You can find good material on the street, why don’t you go look for it?’ So Wechsler decided to make a film about sex crimes against children.

In 1957 he commissioned Friedrich Dürrenmatt to write a screenplay. The police provided the writer with information about a similar case, and this resulted in the film Es geschah am helllichten Tag [It Happened in Broad Daylight], which was released in 1958 with Gert Fröbe playing the role of the murderer. However, Dürrenmatt wasn’t happy with the film, so he re-wrote it in the form of a novel titled The Pledge. Unlike in the film, the perpetrator is never convicted. Many years later, the novel was turned into a film, also called The Pledge (2001), with Jack Nicholson in the lead role.