Nightlife column | City & History

Back when Zurich was silent after 11 pm

Zurich could certainly be considered one of Europe’s most vibrant cities these days: in relation to the number of inhabitants, it has the highest density of nightlife venues of any location worldwide. Our nightlife columnist Alexander Bücheli discusses the times when enjoying yourself after dark was anything but a given.

Zurich nightlife has a long history, with the first taverns existing way back in the 15th century. With the opening of the city in around 1830, the number of venues increased, especially the number of wine taverns. There were no closing times in Zurich between 1888 and 1916, which resulted in a true hospitality boom: in Niederdorf especially, there was one restaurant after another in particular alleyways like the cattle market – in around 1900, there were over 1,000 across the city. And when Palais Mascotte opened on 13 January 1916, Zurich finally had a dancing venue just like Paris and Berlin.

There were no closing times in Zurich between 1888 and 1916, which resulted in a true hospitality boom.

But Zurich wouldn’t be Zurich if, despite the euphoria, the issues associated with nightlife weren’t also passionately discussed – at the time, the main point of deliberation was a question of morals. As a consequence of this debate, there was a vote in 1916 that resulted in a closing time being reintroduced and set at midnight. Dancing was also prohibited on Sundays and Christian holidays. It was only in 1928 that a few dances were permitted once more, with time restrictions of between 3 pm and 6 pm, and 8 pm and 11 pm, which also applied to music.

Socialising after midnight was deemed to be unnecessary, immoral and unhealthy.

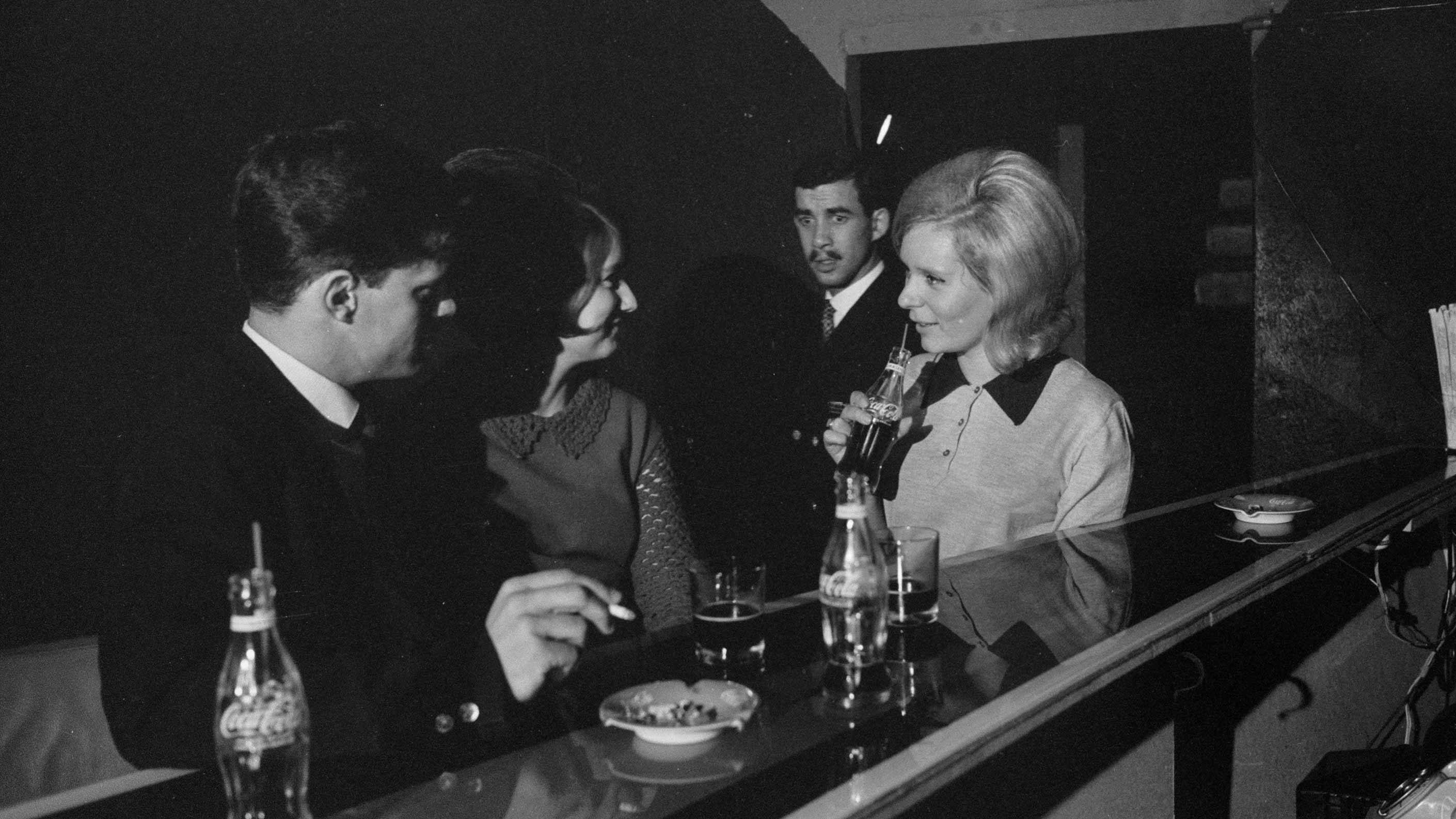

A concert at Nightclub Börse in 1957

From the 1930s, running taverns and restaurants was permitted with a government licence, which was only issued if the establishment met a need and didn’t go against the good of the public – the latter being closely linked with the sale of alcoholic drinks. For this reason, there were a large number of restaurants that didn’t sell alcohol called tea rooms. In 1954, three restaurants were chosen to trial an extended closing time of 2 am. However, the experiment barely lasted a year: socialising after midnight was deemed to be unnecessary, immoral and unhealthy, and closing time was again set at 11 pm under pressure from women’s organisations and pastors’ conventions.

It’s hardly surprising that the number of restaurants plummeted following this decision and stagnated for decades afterwards. In 1960, there was a total of 932 restaurants in the city of Zurich, comprising 775 eateries and 157 alcohol-free tea rooms. (Incidentally, there were only a few more in 1980 with 1,074 restaurants in total, of which 335 were alcohol-free tea rooms.)

The bands The Ladybeats (1965) ...

... and Les Sauterelles (1967) at Road Shark Club

The youth movement of the 1960s brought a flash of life and colour to the otherwise rather dull Zurich night scene, with concerts and festivals featuring heavily on the cultural agenda. Squats like the temporary Globus building and the Lindenhof bunker became hotspots for youth culture. But closing times and rigorous licencing policies continued to apply for licenced establishments as a minimum. It was only after two failed votes in 1959 and 1962 that in 1970, there came success: extending closing time until 2 am became a reality. At the end of the 1980s, there was a further extension to 4 am at the latest, but only a handful of venues benefited because of the necessity clause that was still in force.

There were only four clubs that were allowed to open until 4 am – and even then you could only get the ice and the glass, not the alcohol.

The Zurich of the 1980s was considered vacant, boring to a Zwinglian level. On the route in and out of Niederdorf, only a few restaurants were allowed to serve alcohol. It was generally quite difficult to open up a pub. There were only four clubs that were allowed to open until 4 am – and even then you could only get the ice and the glass, not the alcohol. The frustration of urban youngsters about the lack of cultural leisure options then erupted in the 1980s: the protest movement called for freedom and was aimed at the cultural establishment, venues like the opera house. Following violent demonstrations, the city reacted to demands and with Rote Fabrik and Dynamo, Zurich’s first youth culture centres were established.

2.3

million francs in bribes was pocketed by chief civil servant Raphael Huber between 1982 and 1991.

But there was still a way to go to achieving a relaxation of the hospitality industry law. One of the biggest corruption scandals ever to shake Switzerland was an important chapter in this story: what’s known as the Zürcher Wirteaffäre (Zurich Landlord Scandal). 2.3 million francs in bribes was pocketed by chief civil servant Raphael Huber between 1982 and 1991, and restaurant owners and landlords who greased Huber’s palm received the licences they needed quicker in return. Huber’s rates were steep: according to witnesses, he demanded 50,000 francs for extended opening hours and 20,000 francs for a licence to sell alcohol. This scandal made it clear to everyone how poorly the desires of the urban population in terms of night-time culture were being met by the outdated hospitality law of the time.

It was put to a vote in 1996 and the Zurich people finally said yes to the relaxation of the hospitality law. A deciding factor in this rethink wasn’t just the shift in leisure requirements, but also the hope of the Zurich city population that there would be a revival of the city centre, which had faced an open drug scene and a general exodus during the 1980s and 1990s. Finally, there was nothing more to stand in the way of the success of the Zurich nightlife.