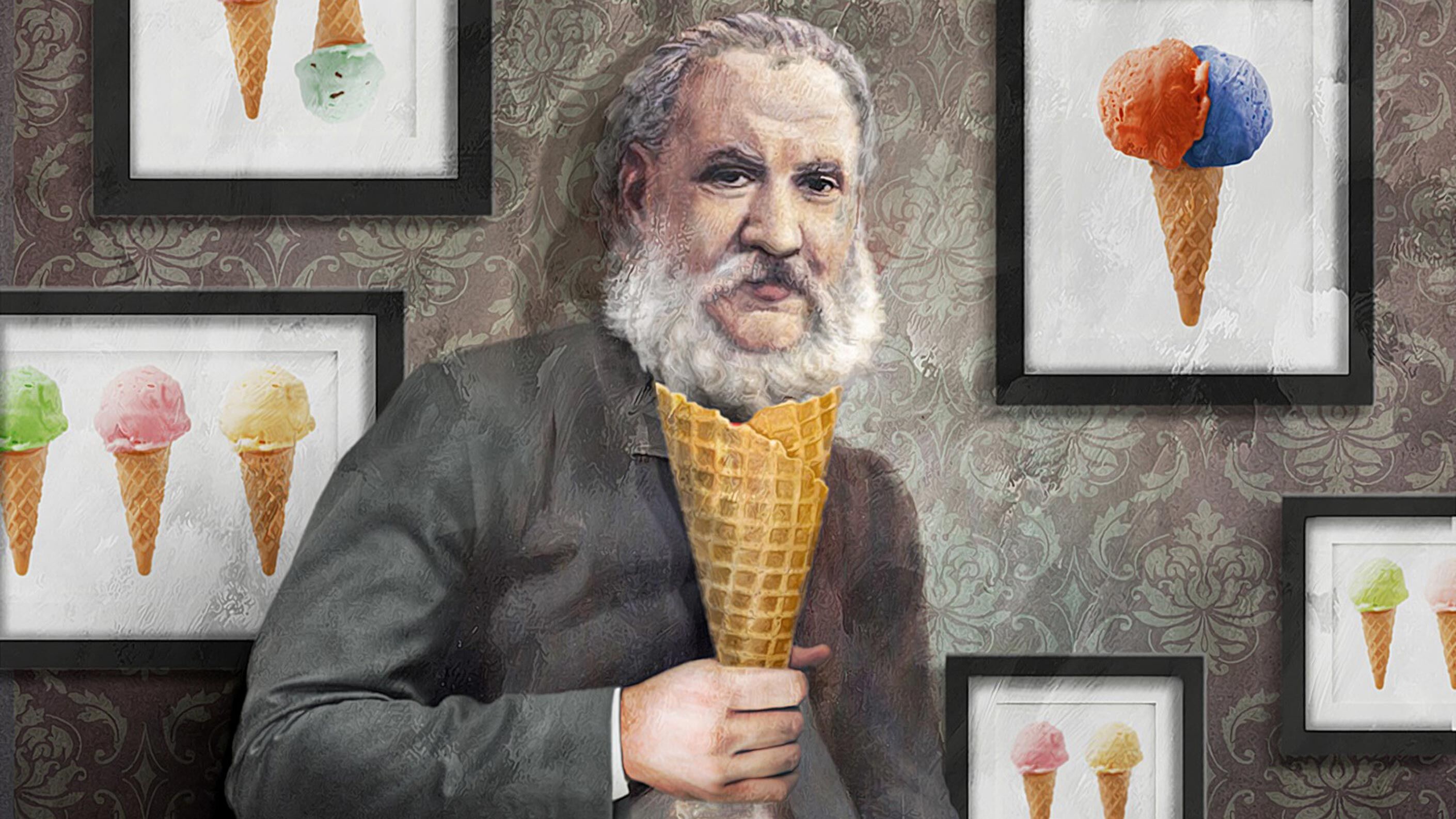

The Ticino glacé king

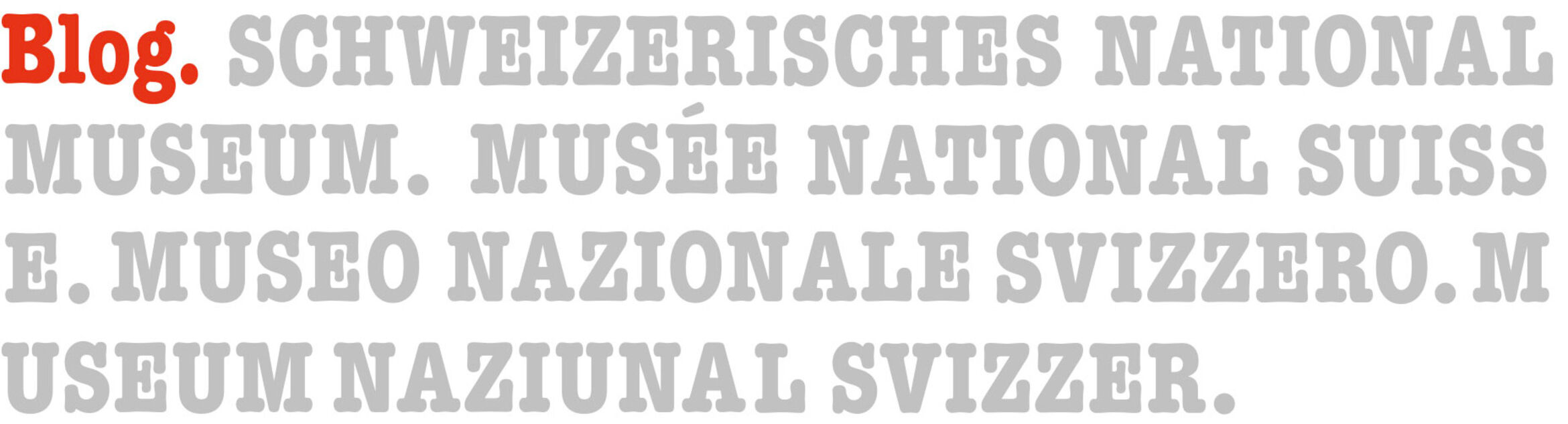

Born in a mountain valley in Ticino, Carlo Gatti moved on to Paris and later to London. He was the first street vendor of ice cream in London, eventually earning a reputation as the uncrowned “Ice Cream King” of Victorian England.

Do you like ice cream? Or as we say in Switzerland: Do you like glacé? It was a Swiss man who first put this sweet treat within reach of ordinary people. But he was a Swiss man far from Switzerland. Carlo Gatti was born in the tiny village of Marogno in the Blenio Valley in 1817, the year of famine. It was a hand-to-mouth existence in this Ticino mountain valley. Anyone who wanted to do more than just barely survive had to leave and emigrate. Carlo Gatti had another reason for wanting to leave: he was a bad pupil, earning frequent canings from the village schoolmaster.

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history here.

Roasted chestnuts were immensely popular in Ticino, but in Paris no one was interested.

So at the age of just 13, he set out to leave his homeland forever. According to some accounts, he was only 12 and couldn’t even write. Fact and fiction intermingle here in Carlo Gatti’s biography.

The Blenio Valley in Ticino, photographed in the mid-20th century. (Picture: ETH Library Zurich)

But what all the sources agree on is that the boy left Ticino on foot and headed to Paris, where he had relatives. In the French capital he lived life to the full, enjoyed gambling, tried his hand at this and that… but time and again, his ventures never quite worked out. For example, selling roasted chestnuts: they were immensely popular in Ticino, but in Paris no one was interested. However, Carlo Gatti learned from his failures what school hadn’t been able to teach him – to be innovative, and to demonstrate that innovation to his customers.

At the age of 30 he decided to move on to London, where the British Empire was enjoying its golden age. In the district of Holborn he ran a vending cart selling coffee and waffles, and he also offered chestnuts. This rather downtrodden part of the city was home to a huge population of Irish immigrants, but there was also a large community of Italians who, like Gatti, were looking for work in the big city.

Fact and fiction intermingle here in Carlo Gatti’s biography.

The Ticino glacé king Carlo Gatti, ca. 1870. (Picture: Wikimedia)

Bit by bit, Gatti continued to make his own luck. Two years after his arrival in London, he and a partner also from Ticino, Battista Bolla, opened a bricks-and-mortar coffee house. And a year later, in 1850, the company started making its own chocolate; the Ticino entrepreneurs “Gatti & Bolla” roasted the cocoa in the shop window of their restaurant, attracting an avid audience. Inside, they also offered sweet confections such as waffles and chocolate, hot drinks and small meals.

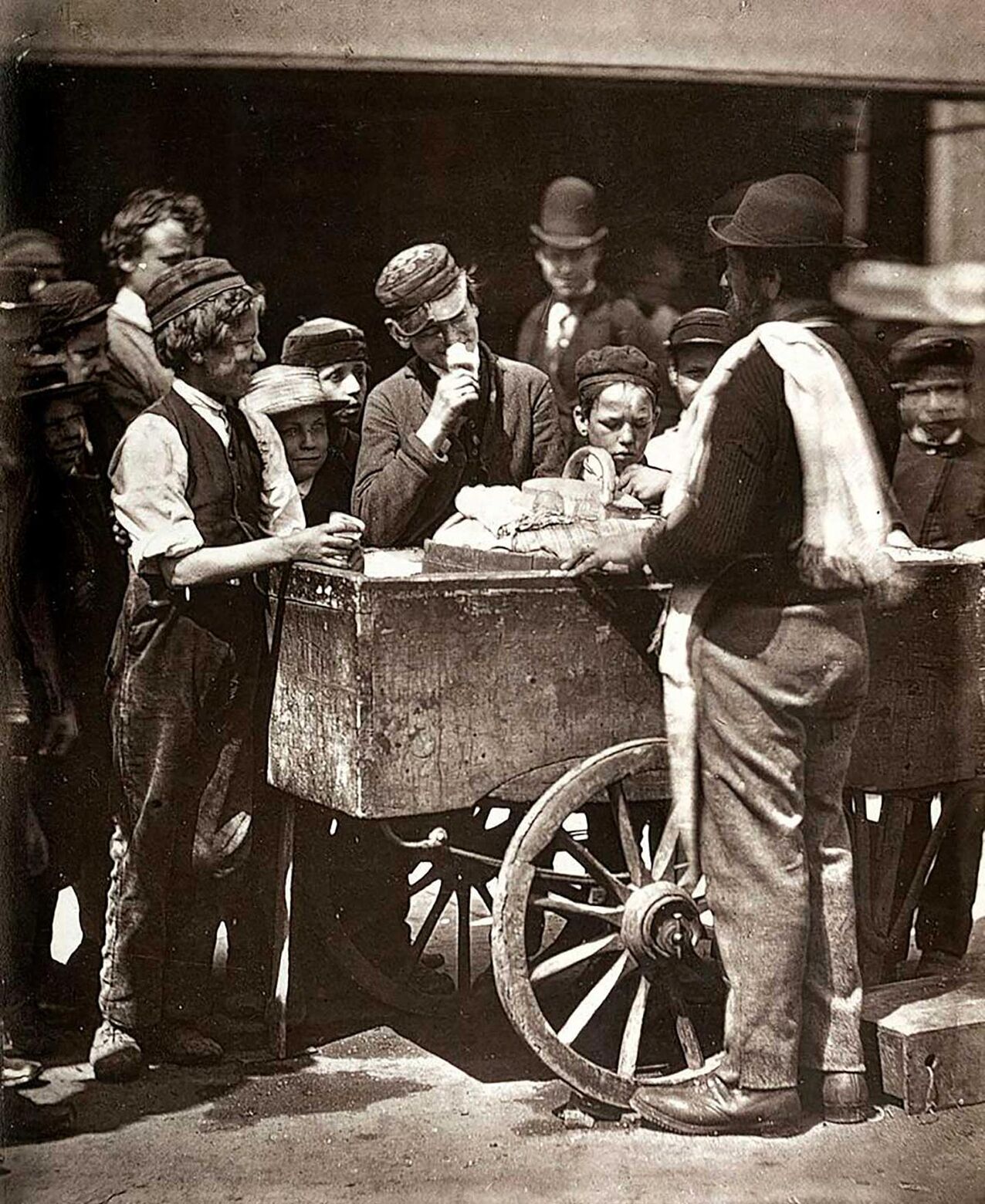

Gatti’s innovation was the cherry on the top of the business’s product range. He sold ice cream, and for the first time the sweet treat wasn’t for kings or other rich people; it was affordable for every man, woman and child. Carlo Gatti democratised the eating of ice cream.

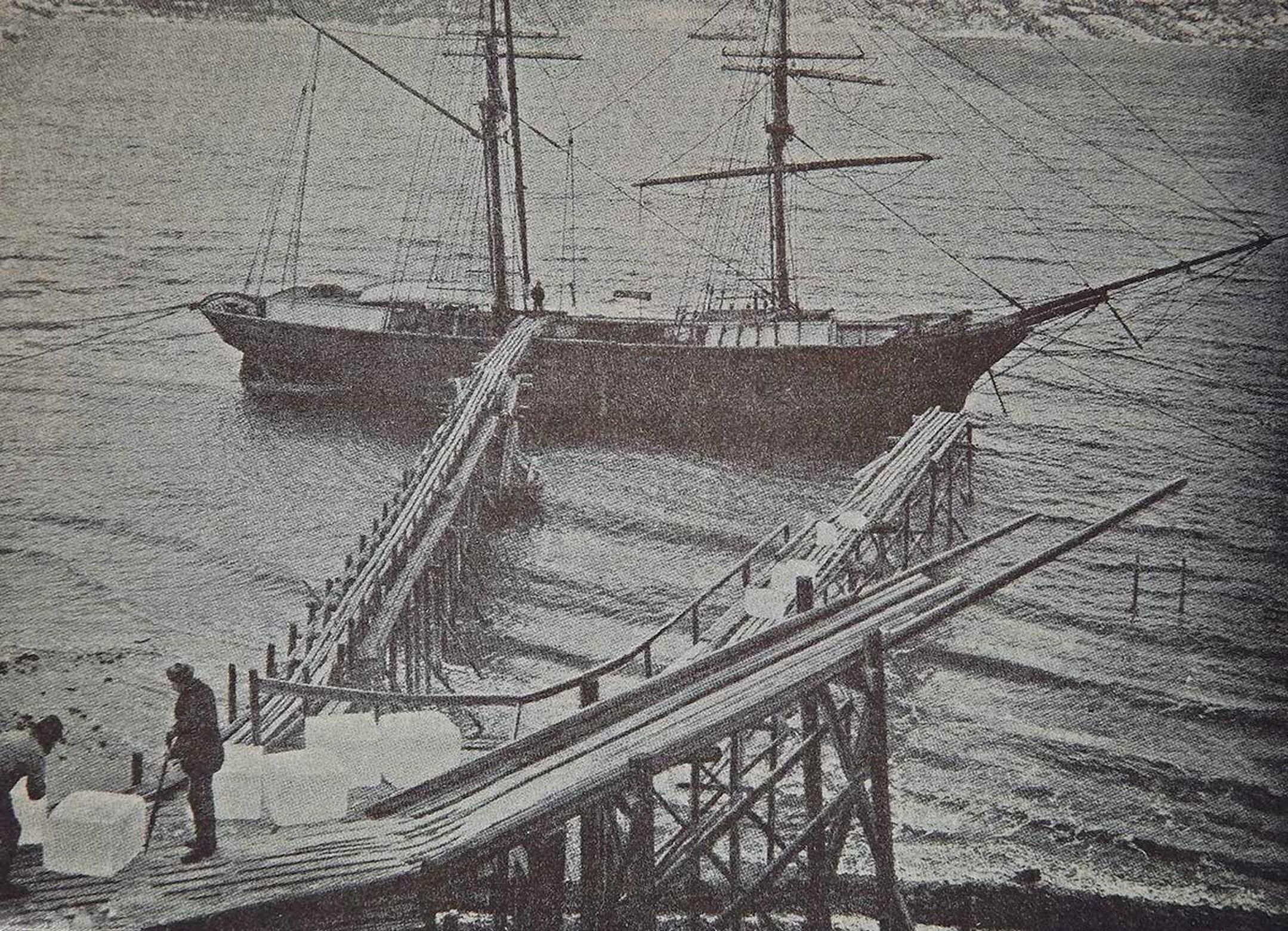

Loading blocks of ice in Norway, 19th century. (Picture: Wikimedia)

The illiterate Swiss man became a multi-millionaire!

It was a costly venture for him, because in those days there were neither refrigeration systems nor ice cream machines. Gatti imported the ice by ship from Norway, and drilled wells 10 metres wide and 13 metres deep in Regent’s Canal where, in an era before electricity, he was able to store the frozen blocks of ice. He also imported an ice cream machine from France, where ice cream, or glacé as it was called there, was still reserved for the rich and famous, but its manufacture was already more advanced.

Gatti’s first taste of success came when he adjusted the price of his product downwards and marketed it accordingly. He charged just a penny, and called his ice cream “penny ice”. Gatti soon had hundreds of Italian ice cream vendors working all over London, and was considered the capital’s uncrowned “Ice Cream King”.

When the 1851 Great Exhibition in London put participating products well and truly in the public eye, Gatti passed all the tests he had previously missed out on: together with Battista Bolla, he presented an automatic ice cream-making machine – what a sensation! After that, the sky was the limit for Gatti and Bolla. They opened scores of cafés, ice cream parlours, and a catering business supplying a private clientele, although their customers also included restaurants, grocery stores and hospitals. Gatti & Bolla also had a whole fleet of horse-drawn carts. In his cafés, Gatti relied on simple food with dishes from mainland Europe at moderate prices. Within a few years, the (supposedly) illiterate Swiss man became a millionaire and then a multi-millionaire!

Carlo Gatti popularised the eating of ice cream: a street scene in London, 1877. (Picture: Wikimedia)

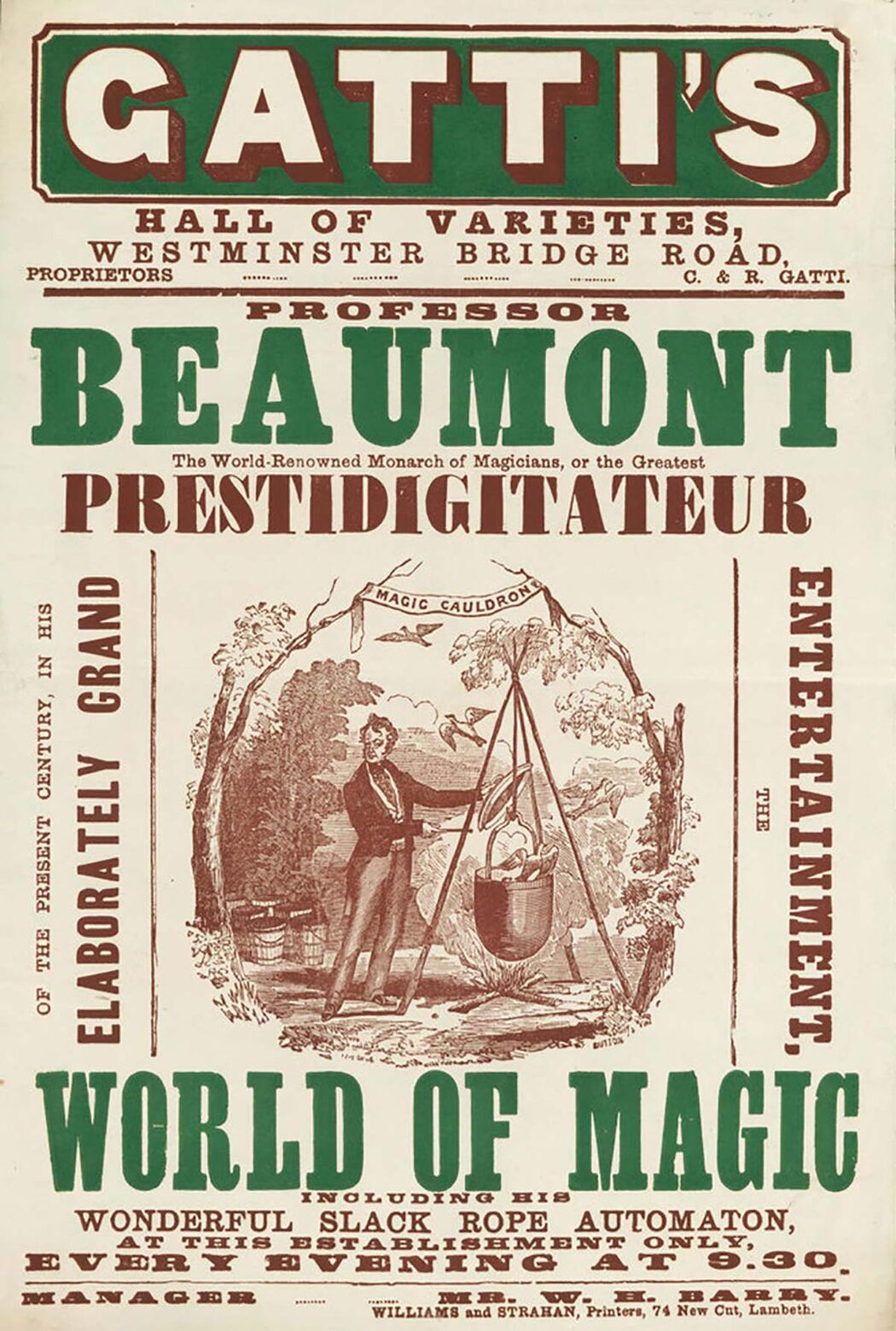

When a major fire destroyed their main business in 1854, it turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Gatti and Bolla: they were fully insured. With the money paid out, they started more cafes, and Gatti began to diversify. He set up high-risk music halls, billiard halls and dance halls – ventures which were also wildly successful. “Gatti’s Palace of Varieties”, “Gatti’s in the Arches” and the “Charing Cross Music Hall” became fashionable gathering places for young people out for a good time.

Gatti became a naturalised Briton. But he never forgot his old home in Ticino, with which he maintained a connection as a sponsor of emigrants from his homeland. He brought in numerous people from Ticino who made a living working in his businesses. In the districts of Strand, Holborn, Lambeth and Islington, colonies of Ticino natives grew up as a result of Gatti’s diverse activities.

Later on, Carlo Gatti also entered the entertainment industry. (Picture: British Library)

In 1871, Carlo Gatti finally returned to the Blenio Valley.

In 1871, Carlo Gatti finally returned to the Blenio Valley, which he had left when he was 12 or 13 years old. Now 54 years old, he married his second wife, Marietta Andreazzi, who was 23 years young. He sat for the Liberals on the Grand Council for two legislative terms, and was a vehement supporter of the construction of the road over the Lukmanier Pass. He wanted to make sure life in the Blenio Valley would be more tolerable and people wouldn’t need to leave, despite his own happy experience with emigrating. In 1878 Carlo Gatti died at the age of 61 as a result of an accident; in Bellinzona there is a large monument in the town cemetery, which still commemorates this energetic Ticino native.